"What's New" Archives: December 2009

December 29, 2009:

December 27, 2009:

December 23, 2009:

December 21, 2009:

December 19, 2009:

December 15, 2009:

Frogs and Faith

I wrote a couple of days ago in my review of The Princess and the Frog about the caution and compromise that wrecked that otherwise promising film. Rod Dreher of the Dallas Morning News has identified one aspect of the film that I didn't discuss but that he sees as suffering from the same sort of clumsiness and confusion that I found so deadly:

The villain, Dr. Facilier, is a big, bad French Quarter voodoo daddy who tries to manipulate evil spirits to do his bidding. When Prince Naveen and Tiana fall victim to Dr. Facilier's spell, who do they turn to for help?

This being New Orleans, you might think that a representative of that city's other rich, venerable religious tradition, Roman Catholicism, would be called on. Anyone who has been to New Orleans knows the place is saturated in the myths and rituals of Catholicism. You have to work hard to avoid seeing what is in front of your face. Bizarrely, Disney creates—wait for it—a good voodoo priestess, Mama Odie, to serve as the film's avatar of white magic and the cursed pair's spiritual guide.

Right, you don't expect Disney films to preach the Gospel. But is the historical expression of New Orleans Christianity so offensive to Disney that they have to substitute a kooky Atchafalaya Oprah? My complaint is not religious, but artistic. Disney's politically correct aversion to Christianity hollows out the potential for spiritual grandeur that ought to have infused this lovely film—and made it something that could stand up against Pixar's best.

I can't believe that any overt references to Catholicism would have been a good idea—I cringe at the memory of the glowing cross at the end of the Prince's fight with the dragon in Sleeping Beauty—but the fact is that some of the most stirring moments in Disney features, like Snow White's awakening and the Beast's transformation, have had an unmistakable religious dimension, calling up as they do thoughts of death and resurrection, with no underlining necessary. The climax of The Princess and the Frog could have struck very much the same note. But, of course, it doesn't.

Reading the comments from the people who worked on the film in Jeff Kurtti's The Art of The Princess and the Frog (and from all the suckups and wannabes who descend on Cartoon Brew whenever a new Disney feature is released), I do have to wonder: Do these people really believe what they're saying? When a film like Princess and the Frog is in production, does anyone ever say, "Wait a minute..." Or is the atmosphere such that any "negative" thinking is discouraged, "positive" thinking being defined as endorsing whatever dumb decision someone in charge has made? And by the time the film is released, has everyone involved, on both sides of the screen, swallowed so much of the company line that they can't tell the difference between the good film that might have been and the bad film that actually exists? I'm afraid I know the answers to all those rhetorical questions.

From Donald Benson: Invoking any specific religion in entertainment—especially the supernatural and the deity himself—is always a minefield. The line between mocking a faith and propagandizing for it is thin and highly subjective. Life of Brian, which was emphatically NOT about Christ, stirred up a firestorm. Wholly Moses, which offered Dudley Moore arguing with a pettily jealous God and consorting with farcical versions of Bible events and personages, came and went like any other dopey Hollywood comedy.

Once you get past dramatizations of the Old Testament and the life of Christ, mainstream films maintain a firm secular reality unless it's a clear fantasy (chatty angels, stylish devils, George Burns and/or a white-robed afterlife) or a horror film (priests versus monsters with varying degrees of effectiveness).

Portrayals of faith run from saintly believers to Elmer Gantry, but the underlying beliefs are rarely if ever affirmed or denied (or even acknowledged, in many cases). This extends to the most overtly religious epics: The Song of Bernadette carefully left room for debate over the miracles; Brigham Young was highly sympathetic to Mormons but avoided presenting Joseph Smith as a prophet. There are exceptions—like the bizarre heaven-and-hell climax of The Black Hole—but in my experience you rarely see "real" acts of God outside of films explicitly targeted to a specific religious audience.

With Princess and the Frog, pitting Catholic faith against alleged voodoo may be historically accurate, but it would also put Catholicism on the same level of reality with those singing masks and dancing shadows. I would guess the Vatican would prefer to not to be invoked in this story (I suspect that Exorcist-inspired hypochondriacs are an ongoing headache as it is, along with the people who think The Da Vinci Code was nonfiction). For all their arcane dogma, modern church leaders seem as skeptical as most laymen when confronted with Christ on a piece of toast, and they're not thrilled when books and movies blithely proclaim the real institution accepts and deals with fictional demons, angels, ghosts, conspiracies, etc.

Also, a church/voodoo special effects battle (as per formula) would play like South Park in full animation.

Targeting Princess and the Frog for this particular offense is like going after any fairy tale that presents magic without all the theological implications of the critic's own faith (Is Hogwarts a satanic outpost?). Or attacking an "uplifting" TV movie because it shows a church but doesn't make it a very specific denomination.

[Posted December 29, 2009]

From Tom Carr: Perhaps I should recuse myself from this discussion because I spent part of my adolescence in a fairly brutal Catholic boys' prep school, and so I'm no fan of the Roman church. The revelations about clerical child abuse (which are still ongoing) that began in the 1990s only reinforced the bad taste that my experience left in my mouth.

Luckily, I was never sexually molested, but I was certainly mistreated in many other ways. Not that I want to dwell on my own past—especially a part of it that I'd rather "erase from the tape" if I could, but this film critic's advocacy for putting a plug for Catholicism in a film that's supposed to be light entertainment for people of all religious persuasions (or none) begs the following question: exactly which side is good, and which side is evil? Perhaps neither is is good, and let me make that point here.

The history of the Christian churches is long and sordid and, especially... bloody. Mark Twain described it in considerable detail in Letters From The Earth, which he withheld from publication until after his death because he was afraid of what the public reaction might have been in a United States that was even more predominantly and devoutly Christian than it is now.

As to Christianity and voodoo (voudoun) in the culture of old New Orleans, let me point out that Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton (1885-1941), arguably the greatest of the early jazz musicians before Louis Armstrong, was raised in a strict Catholic Creole household, but he also believed in voudoun. Morton had a Victor recording contract and many hit records during the 1920s, but after 1930 his career went into a nosedive. Victor didn't renew his contract, he entered into a booking arrangement with MCA that didn't work out, the Depression demolished the live-band business, and even the style of popular music shifted away from hot jazz toward "sweet" bands like Guy Lombardo's and Fred Waring's. Jelly Roll was convinced that someone with "powers" had put a curse on him, apparently because an exterminator had sprinkled a white powder around his office, which he took for "juju powder." (an incident cited in the biography Mister Jelly Roll, by Alan Lomax).

So at least in Morton's case, it appears that these dual sets of beliefs in the supernatural were two sides of the same coin... and aren't all such beliefs the same thing? That is, utter nonsense? I think so. Perhaps they served some useful purpose at some time in the distant past, but then so did the human appendix.

In The Animated Man, you quote one of Walt Disney's daughters as saying that her father wasn't especially religious. Moreover, having been raised in the largely Protestant Midwest at a time when there was a definite antagonism between Protestantism and Catholicism that no longer exists today, I really doubt that Walt would have wanted any specific endorsements of the Catholic church in any of his films. The closest he ever seems to have come to that is the "Ave Maria" monks' procession at the end of Fantasia: a small, muffled coda to what comes before, at most. Perhaps another point of interest is that the Franz Schubert "Ave Maria" is used, rather than the Marian hymn familiar to Catholics (a.k.a. "Immaculate Mary").

However, I'm willing to admit that the producers of the new Chipmunks movie might have some voodoo at their command... how else could it have come in number two at the box office this week!?

MB replies: Some of the comments Rod Dreher's column has provoked from Dallas-area (presumably) readers are rather interesting—most are just dumb, of course, but then there's the one from the woman whose grandchildren were "terrified" by the voodoo in the film:

I will never trust Disney again. I felt like the ultimate grandmother failure not doing my research before exposing my grandkids to this. We should have walked out. Walking into an empty theatre should have been my first clue but I thought that it was due to the cold. I was wrong.

Proof, I suppose, that even in our coarse age some children lead very sheltered lives.

[Posted December 30, 2009]

December 27, 2009:

Foxes and Frogs

I've seen both Fantastic Mr. Fox and The Princess and the Frog in recent days, and I've collected my thoughts about both. You can read my Commentary piece by clicking on this link. Sadly, Princess—a deeply flawed film, but one that's well worth the price of a ticket—seems to have lost the box-office battle not just to Avatar but also to the new Alvin and the Chipmunks movie. I will see that last one only at gunpoint.

From Vincent Alexander: It was great to read your review of The Princess and the Frog. I saw the film recently and was sincerely surprised by how much I liked it. There were some story problems—I agreed with several of the ones you mentioned and there were a few others—but overall I was really happy about how good it was.

The one thing I wanted to comment on, though, was your suggestion that we shouldn't have seen the human version of Prince Naveen until the end of the movie. I'm not sure I agree with you there. A lot of films that dramatically change the way a character looks at the last minute have a way of losing me. You grow to like the character a certain way, and then they alter it and expect you to be satisfied.

For instance, I've always been a bit uncomfortable with the conclusion of Beauty and the Beast when the beast transforms into a handsome prince. After spending the entire film with the beast, it's disconcerting to see him disappear and be replaced by a totally unfamiliar character. Part of the problem on that movie was the almost creepy design of the character (was it just me or did his eyes look empty?), but I think the main issue was just how different he looks.

Don't get me wrong—I agree with you that Prince Naveen's character design as a human is bland, but showing him to us right away strikes me as a smart move.

MB replies: Perhaps the critical problem is that the frog Naveen is so different from—and so much more interesting than—the human Naveen. If they were more readily acceptable as the same character in different guises, the question of when to introduce the human Naveen might be less important.

[Posted December 28, 2009]

From Michael Sporn: Of course, you know that I loved Fantastic Mr. Fox, and my thoughts haven't changed after seeing it a total of three times. We have a difference of opinion that is no less than the difference we have over The Polar Express, but I don't expect to agree with you all the time.

I could only get through 2/3 of The Princess and the Frog on a DVD screener, after having seen it in a theater. The story is so sloppy that it's frustrating to watch. The structure of the film is clumsy, to say the least. The "black experience" is handled so poorly that it was truly annoying. As you mention, seeing blacks and whites mix in a restaurant setting—in that time period—was indicative of the poor research they obviously had done.

Had I done the film, I would have kept Tiana a human—the kiss would have meant nothing—and she would have had to help him get to the swamp woman. (By the way, to me, Andreas Deja's character was the best in the film. Too bad there was so little of her. Instead we have to put up with a sequence of three louts shooting guns—in a children's film—a sequence that still could be cut from the film without notice.)

Despite all my frustration, it was a delight to see 2D animated characters move—and move better than any of the CGI characters of the past ten years. I hope they do more, despite the fact that the film has not been an overwhelming success. It is nice to talk about a hand-drawn film again, despite my lack of enthusiasm. It's still better than Treasure Planet, Atlantis or some of the other dreck that brought the end of an animated era.

MB replies: The high quality of the animation is indeed the best reason to see The Princess and the Frog, maybe the only reason. But the animation is so good that it certainly makes the film worth seeing at least once. I wasn't excited by Deja's animation of the old voodoo woman, but then I wasn't excited by the character, who called up too many memories of the Mad Madam Mim from The Sword in the Stone.

[Posted December 29, 2009]

From a veteran animator who asks to remain anonymous: I finally went to see The Princess and the Frog, and although I wasn't expecting to like it, I was surprised how much I really disliked it. For me the story was a collection of cliches, so much so that it felt like a paint-by-the-numbers pastiche. But even worse was the bad animation. Through most of the film, the characters were just flailing around, with no real acting or real emotion. In the very beginning, before the really bad animation, when we first see Tiana and her mother (who were animated very well), it was jarring to see the white girl in the same scenes whose appearance and movements seemed so contradictory to Tiana's more "sincere" animation—the white girl resembled the shallow and self-consciously stylized drawing and animation of the villain girl from Cats Don't Dance, Darla Dimple.

Once Tiana turned into a frog, the film went so far downhill that it felt like a Ralph Bakshi attempt to make a "zany Warner cartoon," with most of the animation done by Ralph's friend Bob Taylor. Bob Taylor's animation is odd in that when one flips the original drawings, they look quite inventive and expressive, but because of Taylor's complete lack of knowledge of timing, weight, and balance-in-motion, his animation on the screen completely falls apart into chaos.

For me, apart from Tiana as a human (and her family), the only character that I liked was Voodoo Daddy, and his redeeming qualities were mainly his voice and his very expressive gestures; his very erratic movements seemed plausible because his personality and over-the-top gestures seemed to justify such movements. By contrast, the alligator was just falling apart, totally lacking the kind of ballet-like fluidity in motion that I've come to expect from such frenetic characters in the Clampett Warner cartoons.

In short, 99 percent of the film cried out for subtlety in the sincere scenes and fluidity in the wacky scenes, which were so glaringly absent.

[Posted December 30, 2009]

From Bill Benzon: I enjoyed your remarks on The Princess and the Frog, especially on the quality of the animation (where your eye is more acute than mine). They helped me make sense of my own somewhat mixed reaction. As for Avatar, which I've seen in 2D, every time one of these mega mega budget films comes out I wonder whether or not we'd be better off with ten different films at a tenth the budget— that way there's a chance that one of them would actually be good and two or three others at least interesting. Avatar did not disappoint on THAT score. Special effects were excellent, perhaps Cameron hasmoved mocap up a notch, but the story it self . . . .? What was unexpected was how much of it looked like live action Miyazaki. It looks like Cameron has copped a lot of imagery from Princess Mononoke, along with the forest mysticism, Castle in the Sky (floating mountains), and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, glowing tendrils with healing power. Just what this CGI tech portends for films in general, who knows? But it does seem to mean that, at this point, live action films can be placed in any world you can imagine as freely as animated films . . . as long as you're willing to pay for it. And that cost will come down over time.

MB replies: I still haven't seen Avatar, but my curiosity has been thoroughly aroused by now, so no doubt I'll see it soon, especially while it's still playing in 3D Imax.

As to the quality of the animation in The Princess and the Frog...my anonymous correspondent, in the comment posted just above Bill Benzon's, would probably disagree that my eye is acute, at least in this instance. And certainly there's poor animation in the film, of poorly designed characters (like the three bayou rustics) that would fit right into a recent Disney disaster like Home on the Range. Likewise, I can't work up the least enthusiasm for Mama Odie, either as character design or as animated by Andreas Deja, and I am baffled by the praise I've read for the design and animation of Charlotte, Tiana's rich white girlfriend, whom I find intolerable as both child and adult; she is to me the one conspicuous relic in the film of the Bluthian aesthetic that confuses self-consciousness with "personality." But it's Tiana, as a human character, and the two frogs (and secondarily the alligator) who bear the weight of the film, and I don't see a crippling fault in the animation of any of them.

I think the temptation is always to look at something like Eric Goldberg's animation of Louis the alligator, or Randy Haycock's animation of the frog Naveen, and measure it against animation of roughly comparable characters in other films, some of which may be clearly superior on its own terms. But the real test, I think, is, how good is this animation when measured not against some essentially abstract standard, but against this particular film's requirements? I think Princess's most important animators pass that test. Their animation is at least as good as the muddled story deserves, and usually much better.

[Posted December 31, 2009]

From Geoffrey Hayes: Once again, your comments have helped expand my understanding of Disney animation. I'm glad there were at least parts of The Princess and the Frog you enjoyed, because there was much in it that I did, too. I was impressed, as you were, by how Princess developed the main characters' relationships. And sort of surprised to find myself by the end rather fond of Louis the alligator and Ray the lightning bug. Unlike many, I wasn't aware of the story flaws, but found myself caught up in the adventure. Perhaps on a second viewing these will become apparent. I've been writing and illustrating children's books (and comics) for thirty years, so generally I'm most critical of the script. However, story holes in Disney are nothing new. As a kid I simply couldn't understand why Sleeping Beauty's Three Good Fairies didn't wait until after sundown to return her to the castle. I mean, sixteen years of diligence, and they blow it at the last minute? Surely the writers could have found a more plausible way for Maleficent to get to her.

What I found most pertinent in your review were your remarks about Disney playing it safe. It may have seemed like a good idea to test the waters by giving the public a traditional Disney 2-D movie. But it isn't, as they say, "sexy." It's heartbreaking that this lovely, though flawed, film is struggling to make 100 million while drek like The Chipmunks is raking in the bucks. Yes, I believe that the creative staff is lulled by the company line. I know it's difficult to be objective while you are in the midst of creating, but someone has to be. At the moment, I blame John Lasseter. He is at heart creatively conservative. In fact, Disney's animated films of the '90s were much bolder design-wise than anything Pixar has attempted. It didn't always work, but I applauded them for attempting new things.

Lasseter never goes far enough. It looks like he's at work again, judging by the newest still from Rapunzel to hit the web. For years, I've read about how Glen Keane was going for a painterly style. How cool would that be, to have a computer-animated film that didn't look computer animated! So what do we get? A clearly CGI film with characters who mimic hand-drawn! Now, perhaps I'll happily be proven wrong and Rapunzel will turn out to be something innovative, but I'm not holding my breath. Judging by Disney's current B.O. track record, innovation may be what the public is looking for. "Hey! An animated film that looks like a painting in 3-D! Never seen that before!"

The sad thing is that Lasseter believes his own press. I heard him say that Disney/Pixar is a director-based studio, which would imply individual visions. Then he goes and replaces Glen Keane (who did have a vision for the film, even if it wasn't working) with two company directors who had just come off the mediocre Bolt. Sadder still that there's no one out there who can really replace John Lasseter. What he does, he does better than anyone in the business. To quote a Disney song, he just doesn't "Go The Distance."

[Posted January 4, 2010]

From Geoffrey Hayes: I wholly agree with your take on Mama Odie. She was the least interesting character, design- and animation-wise. And I also agree that Charlotte as a child felt out of place with the characters around her; however, in keeping with your stance that the main characters' animation suited, or surpassed, the script, why don't you feel this way about the adult Charlotte? She is a self-conscious character. I thought her animation reflected this, and wasn't really Bluth-inspired so much as it was an expression of her personality. Although I do question the filmmakers' decision to play her so over-the-top. One more plus for this movie is that the story at least wasn't pretentious. It wasn't aiming to be an epic or to hammer home some moral. I enjoyed it on that level.

MB replies: I think there's a difference between a self-conscious character and self-conscious animation, and Charlotte, as child and adult, struck me as an example of the latter—that is, the kind of animation that insists too much on our awareness of the animator, and the animator's "sincerity," and diminishes the character. But maybe I'm being unfair. I do want to see Princess and the Frog again, I hope in a theater but if not, then on Blu-ray, and I'll post a few second thoughts then.

[Posted January 7, 2010]

From Roberto González Fernández: I've been reading your commentaries about Princess and the Frog which I finally could see here in Spain. I agree with a lot of your comments about the movie, but I feel like defending Mama Odie's character a little. I'm not the biggest fan of her design, because I don't usually like characters who have "realistic" details like too many wrinkles, but I enjoyed her animation for the most part. I also think she has one of the best songs and she was a pretty likeable character. One thing that surprised me is that I was expecting her to appear a lot more in the picture. However, I kind of felt satisfied with her little role. That's because it was pretty well done. The lyrics of her song were interesting because she revealed the message of the film without getting overly preachy about it, and she kind of predicts what's going to happen during the last half without spoiling everything to the viewer. As she sings, people tell her "what they want" and she gives them "what they need." She could have probably turned the main characters into humans right away, the way she changed the snake several times during the song, but instead she wanted them to learn a lesson. Naveen has to forget about money and think about love, and Tiana...well, I didn't quite get what Mama Odie tried to say to her but I understood something like this: "OK, you have been a swell girl working all your life to get the restaurant like your daddy wanted, now you can relax a little and marry this guy if he truly loves you." I liked how Mama Odie actually reappears at the end, that kind of makes sense, she really wanted to help them to become human again but only after they had learnt their lesson. All this makes her a wise and likeable character.

As for the rest of the movie it was...odd. It had some good qualities but it seems everything could have been a little better. The premise leads to a mixed movie since it has to be about the characters as humans and the characters as frogs. As a result I felt the first part—the most "traditional" one—of the movie was a little rushed. Nothing happens in the bayou, they just met the sidekick characters, everyone sings a song and that's all. They totally wasted Louis's character, to me a jazz-singing alligator is actually a good idea. But they don't let him be a great character like Baloo in The Jungle Book. He's limited by his sidekick condition, so he is only there to make funny faces. I agree with everyone about his animation. Sometimes it was very funny but he just moves too much all the time. On the other hand they gave quite more development to Ray, who is a less interesting character in theory. I didn't quite get why they decided to give him such an important role, I mean, his arc was nice and everything but I don't think this character was so important after all. At least Louis wants to be a human like the main characters, Ray just meets them for some reason.

That was the second part of the story, when they seemed to get rid of the songs, which are the best part of the first half, and they introduce more "experimental" things in the storytelling. I think this part was maybe a little stronger, but it also felt a little weird, because it wasn't as classic and we're not so familiar about the plot points here. Still the songs and the musical numbers are the best part overall, but this last act had some interesting experiments.

I quite liked Dr Facilier, though maybe a little more of a backstory for him would have been interesting.

I completely agree with you about the race issues, I think it was pretty disappointing on that aspect. I wasn't expecting a realistic drama but they should have shown a little more about the issues of black people at that moment. I also think Naveen should be more of a black person instead of a dark-skinned Aladdin. I would have probably picked one movie instead of two. Either "the frogs go to see the witch lady movie" or "the black girl confronts the evil voodoo man,,,and maybe there is a frog prince there... movie". Those are my two cents...

[Posted January 27, 2010]

December 23, 2009:

Christmas with Kalle Anka

From my friend Roger Webb, this link to a Slate story about the curious Swedish affection for the 1958 Walt Disney Presents episode called "From All of Us to All of You" (also known as "Jiminy Cricket's Christmas" in its VHS and laserdisc incarnations). I'm tempted to say something about the maddening effects of those long, long winter nights, but I don't want to risk insulting my Swedish visitors...

From my friend Roger Webb, this link to a Slate story about the curious Swedish affection for the 1958 Walt Disney Presents episode called "From All of Us to All of You" (also known as "Jiminy Cricket's Christmas" in its VHS and laserdisc incarnations). I'm tempted to say something about the maddening effects of those long, long winter nights, but I don't want to risk insulting my Swedish visitors...

(That's Kalle Anka, better known in the U.S. as Donald Duck, at the right, with another Disney character that the Swedes supposedly confuse with Woody Woodpecker. But you know who it is, don't you?)

From Gunnar Andreassen: You better not elaborate more on your not too nice comments about this Swedish Christmas tradition, or else you might insult your Norwegian visitors as well! If Swedes are a little special in their heads, this certainly goes for us Norwegians as well.I have been watching this show since the early 1960s—for nearly 50 years—and every year on Swedish television.

In the early years this show was only broadcasted from Sweden, but also watched by a large part of us Norwegians. Later on there has also been an annual showing of it here with us, but a lot of us still watch the Swedish version, as we have no problem understanding Swedish.Today my children and grandchildren are coming to us for Christmas celebration—just in time for all of us to watch this show.

Here’s a link to Swedish Wikipedia’s article about it. At least you can see how many Swedes that watch it every year. The Swedish population is ca. 8 millions.

It would not surprise me if you get comments from other Swedes and Norwegians! By the way, I have never heard of anyone that has confused this strange bird with Woody Woodpecker.

[Posted December 24, 2009]

December 21, 2009:

Mintz Meat

In my rush to put up my November 30 post of a photo I titled "On the Sidewalk with Charlie Mintz," I forgot about Mark Mayerson's 2006 post of three photos—provided by Paul Spector, Irv Spector's son and the proprietor of a blog about his father—that were also taken in front of Mintz's Screen Gems studio at 7000 Santa Monica Boulevard. Comparing how some of the people in all these photos are dressed, like Irv Spector and Ed Rehberg, it seems highly likely that all four photos were taken within a few minutes of each other.

The photos must have been taken sometime between 1933 and 1936. Judging from the entries in the Film Daily Year Book, the Mintz studio moved from 1154 N. Western Avenue to Santa Monica Boulevard in 1933; and according to Paul Spector, Irv Spector had left for the Schlesinger studio by '36.

As to what might have driven everyone out of the studio and onto the sidewalk, I suggested it could have been something like a cel fire, but Jenny Lerew has offered a more plausible suggestion: an earthquake, perhaps the very destructive Long Beach earthquake of March 10, 1933, or, more likely if that was the 'quake, an aftershock, since the Long Beach 'quake occurred just before 6 p.m. (I've experienced only one mild aftershock in all my visits to Los Angeles, but that was enough.) If the Long Beach 'quake was the cause, the Mintz studio must have moved to Santa Monica Boulevard by early in '33. A subject for further research.

Cel fires were certainly not unknown at the Mintz studio in the '30s. Here's a photo, lent to me by the late Mary Cain (who worked at Screen Gems for about ten years before becoming ink and paint supervisor at the new UPA studio), that shows a cel fire on April 26, 1938:

In 1940, after Charles Mintz's death, the Screen Gems studio—by then wholly owned by Columbia Pictures—moved from Santa Monica Boulevard to 861 Seward Street, occupying quarters that later housed the Walter Lantz studio, after Lantz moved off the Universal lot.

And on the subject of Mintz...no one with the slightest interest in that studio, or animation history generally, should miss Joe Campana's extraordinary post pinpointing where some photos of the Mintz staff were taken in the very early '30s, when the studio was still located on Western Avenue. There have been no Campana posts for more than a year; I hope we haven't seen the last of them, since they illuminate Hollywood animation history in the way no one else's blog does.

December 19, 2009:

Richard Todd

Richard Todd, the star of three of Walt Disney's first live-action films, died in England on December 3, at the age of 90; the New York Times obituary is at this link. He appeared in The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), The Sword and the Rose (1953) and Rob Roy the Highland Rogue (1954). He appeared in many other films, too, and was nominated for a best-actor Oscar for his role in The Hasty Heart (1949). He was a true war hero, as one of the first British paratroopers to land in Normandy. He was, in short, a dashing and glamorous figure, and, as my wife and I learned on June 22, 2004—just a few weeks after Todd took part in ceremonies commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day—a delightful luncheon companion.

We were in England during an extended research trip to Europe, for The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, that had already taken us to France, Switzerland, and Denmark. I had been in touch with Todd by mail and email for some months, and we had agreed to meet for lunch at Grantham, in Lincolnshire, about an hour's train trip north of London, near Little Humby, the village where Todd was living then. We'd had no confirmation from Todd of our plans in the days just before our scheduled meeting, and so Phyllis and I felt some apprehension when we got off the train at Grantham.

We were in England during an extended research trip to Europe, for The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, that had already taken us to France, Switzerland, and Denmark. I had been in touch with Todd by mail and email for some months, and we had agreed to meet for lunch at Grantham, in Lincolnshire, about an hour's train trip north of London, near Little Humby, the village where Todd was living then. We'd had no confirmation from Todd of our plans in the days just before our scheduled meeting, and so Phyllis and I felt some apprehension when we got off the train at Grantham.

We needn't have worried. Waiting on the platform for us was a very dapper elderly man, using a cane but immediately recognizable as Richard Todd. As Phyllis said—she had become a fan as we watched a dozen or so Todd movies in preparation for the trip—he still had those twinkling blue eyes. His handsome necktie, he told us later, bore the insignia of his Royal Air Force unit.

Todd drove us in his Mercedes to the Angel and Royal, an 800-year-old Grantham hotel where King Richard III once held court in what was now the main dining room. It was closed for lunch, unfortunately, and so we would have lunch in the bar. As we waited for our table to be made ready, Todd suggested rather gingerly that perhaps we might have something to drink before lunch. When I proposed Bloody Marys, he readily assented.

We talked about Walt Disney and the Disney films over the excellent lunch that followed, Todd expanding on what he had already written about his Disney experiences in the two volumes of his autobiography, Caught in the Act and In Camera (neither of which was ever published in the U.S., although copies are available through used-book dealers). You'll find quotations from our interview in The Animated Man, along with a photo of Todd with Walt at Coney Island, which he sent me later.

As I listened to Todd at lunch, and a few weeks later on tape, the years fell away; his voice was still that of the strikingly handsome young actor who was easily the most successful Robin Hood on the screen, excepting only Errol Flynn (the publicity photo at left above is of Todd in that role). At 85 he was still very much a movie star, in other words, and in the best sense: not as an ego but as a presence. I'm grateful that I got to spend a couple of hours with him.

After lunch, Phyllis and I took photos of ourselves with Todd; that's her with him in the photo above. And then Todd drove us back to the Grantham station, for our return trip to Kings Cross station. A lovely day.

Of Todd's three Disney films, only The Story of Robin Hood has been released on a generally available DVD, in a disappointing transfer. Rob Roy is on a Disney Movie Club DVD (which can be bought used through amazon.com, but at an exorbitant price). The Sword and the Rose is available on DVD only as a Hong Kong import (again at an exorbitant price). It's a pity that the Walt Disney Treasures DVD series is winding down; a two-disc set of the Todd films, with appropriate extras (perhaps under a title like "Walt in Britain") would be an excellent tribute not just to Todd but also to the late Ken Annakin, who directed Robin Hood and Sword and the Rose, and might find an audience appreciative of the films' low-key charms.

Roy Edward Disney

I never met Roy Edward Disney, who died this week at the age of 79, and I never tried to meet him, even when I was writing books devoted in large part (Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age) or entirely (The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney) to the animation studio that his father, Roy O., and his uncle Walt founded and that bore the family name.

There were reasons for that. For one thing, as I wrote in my review of Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, "at the time I was conducting interviews for The Animated Man [Roy] was engrossed in the 'Save Disney' campaign, and he was using his Uncle Walt's memory as a weapon against the Walt Disney Company's CEO, Michael Eisner. Trying to collect illuminating anecdotes under those circumstances seemed like a fool's errand." And there was something else.

There were reasons for that. For one thing, as I wrote in my review of Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, "at the time I was conducting interviews for The Animated Man [Roy] was engrossed in the 'Save Disney' campaign, and he was using his Uncle Walt's memory as a weapon against the Walt Disney Company's CEO, Michael Eisner. Trying to collect illuminating anecdotes under those circumstances seemed like a fool's errand." And there was something else.

In all the research I did, Roy E. Disney was all but invisible. He worked at the Disney studio starting in the 1950s, but the many people I interviewed and the many documents I read said nothing about him. His name almost never came up even in the interviews conducted soon after Walt's death by Disney-blessed writers like Richard Hubler and Bob Thomas, who had access to family members and friends who rarely talked to anyone else. Ron Miller, Walt's son-in-law and chosen successor, was a much stronger presence in everything I read.

Perhaps Roy Edward's very low profile in those years was through his own choice. In later years, after Walt Disney and Roy O. Disney died, he achieved very high visibility through his two successful campaigns against its management—first Ron Miller, then Eisner—and his support of the studio's animation division.

I've never been sure how seriously I should regard Roy E. Disney as a champion of either the Disney legacy or Disney animation in particular. His pet project, Fantasia 2000, was not nearly as ambitious or successful, artistically, as the original Fantasia (itself a decidedly mixed bag, of course). The most provocative take I've read on Roy E.'s role at the Walt Disney Company is at this link, via Michael Sporn's "Splog." Future historians will no doubt sort it all out, if the Walt Disney Company lets them.

But I'm sorry now that I never asked Roy for an interview. When I've seen him on camera in the last few years, as in the wonderful DVD sets of the Disney True-Life Adventures, he has seemed remarkably frank and natural—still not someone who could have told me much that I wanted to know for my two books, but someone who would have been enjoyable and interesting to listen to. Most likely Roy would have turned down my interview request, since by the time I began work on The Animated Man Neal Gabler had already won his cooperation; but maybe not.

From Dana Gabbard: I now devote a lot of my free time to issues relating to public transportation in the L.A. area. Once this entailed attending one of those good government type panel discussion events in West Los Angeles. Before the main event started the person seated next to me, a young chap, mentioned in casual conversation that he worked for Roy Disney (likely his holding company Shamrock). I asked had Roy given any thought to doing an autobiography. He responded this has been broached with Roy before but that Roy evidently was modest and demurred at the idea. Which is a shame. At the very least it might have provided us with a fuller picture of his father than the somewhat disappointing biography Bob Thomas did of Roy Sr. some years ago.

[Posted December 25, 2009]

December 15, 2009:

Back Again...

...more or less, although Christmas keeps getting in the way of my intention to write something here. I've seen the new Disney feature The Princess and the Frog since Phyllis and I returned from a short trip, and although I found in that film considerable food for thought, it'll be later this week before I can assemble a coherent review. (In brief: I liked it better than I expected).

...more or less, although Christmas keeps getting in the way of my intention to write something here. I've seen the new Disney feature The Princess and the Frog since Phyllis and I returned from a short trip, and although I found in that film considerable food for thought, it'll be later this week before I can assemble a coherent review. (In brief: I liked it better than I expected).

The occasion for our visit to our old home town of Alexandria, Virginia, was the annual Scottish Christmas Walk, a parade filled with bagpipes and kilts and Scottish terriers and other reminders of the city's colonial origins as a seaport founded by Scottish merchants. This year's route, as in most years, brought the marchers past our former address on Saint Asaph Street, in Alexandria's Old Town, but the parade started in rain and continued in snow. Not as much fun as usual, even with the helpful warming provided by one of our former neighbors in the shape of a hot scotch toddy.

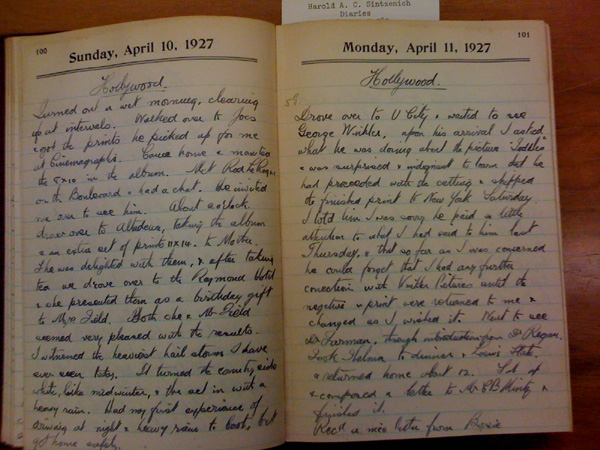

As always when I'm in the Washington, D.C., area, even for a few days, I find time for the Library of Congress. One of my targets this time was Hal Sintzenich's diaries, whose presence in the LC's manuscript division was pointed out to me by J. B. Kaufman.

I wrote about Sintzenich in a September 20 post, after my last visit to the LC, when I found his photo on the same page as Walt Disney's in an advertisement for Winkler Pictures in the 1927 Film Daily Year Book. Sintzenich and Andrew Stone were shown as directing two live-action "two-reel novelties" each for Winkler—that is, for Walt's old nemesis Charles Mintz, who ran the company that distributed the Disney "Alice Comedies." Those four live-action short subjects were to be released through Paramount, which was also releasing the Krazy Kat cartoons that Mintz produced in New York.

According to a press sheet filed when the four films were copyrighted, there were to have been ten Mintz-produced "novelties" altogether in Paramount's 1927-28 release schedule, half of them of "the heavy drama type" and half "in the lighter vein," but I know of only the four. Both of Sintzenich's films, A Short Tail and Toddles, were "in the lighter vein," with casts dominated by children and small animals; Stone's two films were of "the heavy drama type."

I was curious whether Sintzenich and Walt Disney ever crossed paths when both were making shorts for Mintz. The answer is, probably not. That was a question J. B. Kaufman hadn't explored, since he examined the diaries from the earlier period when Sintzenich was a cameraman for D. W. Griffith.

Sintzenich made A Short Tail in New York in 1926, then took the train west in January 1927 to make Toddles in California. During his first few weeks in Los Angeles he spent a great deal of time with Mintz's brother Nat and brother-in-law George Winkler, but I found no references to Walt in the diary pages for that period. (It was presumably Nat's involvement with the live-action shorts that earned him his title "manager of production.") That's not to say that a more careful examination of the diaries might not yield at least an oblique reference to Walt, but if it's there, I missed it.

What was obvious from the diaries, though, was that George Winkler vexed Hal Sintzenich in much the same way that he vexed Walt Disney and Hugh Harman and other people who made cartoons for Mintz over the years. George evidently considered himself a crackerjack film editor, and Charles Mintz supported that judgment. Sintzenich did not share it, as the diary entry for April 11, 1927, makes clear:

And speaking of the Library of Congress...there's a small but quite nice animation-related exhibit there now, in the Performing Arts Reading Room, called "Molto Animato: Music and Animation." It'll be up through March 28, 2010, and you should allow thirty minutes or so to see it. I didn't allow enough time, and I had to leave a little frustrated.

The Hot Air Express Rolls On

Because I was about to leave home, and then was gone, I missed an opportunity to post a comment in the online debate at Cartoon Brew between Stephen Worth and David Gerstein about whether "text documents" have ever played a creative role in animation production. (The Worth-Gerstein exchange is still available, but when a post slides off Cartoon Brew's front page it almost always ceases to be a live subject for discussion.) For the record: everything David Gerstein says is correct, and Stephen Worth is, as is so often the case, wrong in every particular.

Worth is no longer claiming, as he did for a long time, that scripts for animated cartoons didn’t even exist before 1960. But to say, as he does now, that “text documents did not serve a creative role in the development of story in animated films…they served an organizational role” is equally false.

This question of the role of “text documents” in work on golden-age Hollywood cartoons was hashed out on my Web site and others almost two years ago. If you want to read what was being said then, I’d suggest you go to my January 10, 2008, posting—and work your way forward or back or out to other blogs, as you see fit. I’ve also reproduced a number of documents from work on one cartoon, Disney’s Who Killed Cock Robin?, at this link.

Worth claims expertise from whatever it was he did in TV animation, but he's like a burger flipper offering himself as the second coming of Julia Child. The stale gossip he peddles, some of it ostensibly based on what he heard from Otto Englander's widow, Erna, is particularly offensive. He denigrates Dick Creedon, an important member of the Disney writing staff in the '30s, but can't even spell his name correctly. Over and over again, Worth shows that he simply doesn't know what he's talking about.

Worth presents himself as an "archivist," a custodian of animation's history, but his arguments are those of someone who is interested not in historical accuracy but in promoting himself and his patron, John Kricfalusi. John K. believes good cartoon stories cannot be written but must be drawn; the classic Hollywood cartoons are the best ever made; therefore, whatever the evidence to the contrary, those classic cartoons cannot have been written! To get new cartoons as good as the old ones, we must entrust the task to John K., the only director in contemporary animation who understands that text documents cannot play “a creative role in the development of story in animated films”! That is not an argument that everyone will find persuasive.

It sickens me that a few innocents have entrusted Worth and his "archive" with documents of genuine historical value. A while back, I speculated here about where I might eventually deposit my own research materials, which after more than forty years now include, among a great many other things, hundreds of tapes and transcripts, thousands of photos and letters, and tens of thousands of documents and clippings. I heard from someone named Bill Turner, with ASIFA-Hollywood, who suggested that I donate everything to Worth's "archive." I'd rather burn it all first.

From Darrell Van Citters: I’m in complete agreement about the ASIFA archive. It’s really run as Worth’s private collection, not accessible to researchers, and I tell everyone who even thinks of donating to find a more worthy source. What this medium needs is a real home for all the seminal animation collections that have been assembled.

MB replies: Darrell's own contribution to animation history, Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol: The Making of the First Animated Christmas Special, has been getting rave reviews and is available now through amazon.com, at this link.

From Ricardo Cantoral: Steve Worth is doing as much injustice to animation as the current reigning network executives running the most creatively bankrupt networks. I think a quote from a movie I saw recently involving some of the worst propaganda in the 20th century is valid here and what Worth believes, "If you say something over and over again, it becomes the truth."

From Tom Carr: I don't want to get in the middle of an internecine squabble about cartoons, what I'd like to do is just enjoy them. So, to say exactly what I've been trying to avoid saying (!?), aren't many of the best old classic cartoons neither completely scripts nor storyboards? Rather, something in-between? (no pun intended, but there it is).

That is, what we have other than the finished products are basically, fragments. Walt Disney was renowned (in-studio) for being able to act out all the parts in his films, and then his artists took it from there. Max Fleischer even played the straight man to KoKo the Clown, but how much pre-production planning was involved? Not a whole lot, apparently, which is what makes those little films such great entertainment even today.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wanted all of his papers burned after his death. He said, "All that should remain is my decisions. How I got there is no one else's business." Maybe animated cartoon directors should maintain the same principle? Oh... quoting Holmes is too heavy for this subject.

So I'll finish by saying that I just watched the latest DVD remastering of Snow White, and it's gorgeous—Walt's magnum opus probably looks and sounds better here than it did in 1937 (digital vs. mechanical reproduction). But all the included promotional material for The Princess and the Frog doesn't make the new film look very good by comparison. The simplicity and directness of the original Disney storytelling style have been lost.

MB replies: The point of what a number of us have been saying in rebuttal to Steve Worth's ridiculous assertions is not that cartoons were written rather than drawn, but that writing as well as drawing was an important part of the creative process in the "golden age." More important in work on some cartoons than others, but important. The "fragments" can't tell us everything—we can know what Walt said in story meetings, but how he said it may have been just as important, and that's much harder to recapture—but they can tell us a great deal; and one thing they tell us is that many of the creative people at Disney's, in particular, had no qualms about relying on words as well as, or instead of, drawings to put across their ideas. Whatever worked.

From Peter Hale: What a hoohaa! This comes across as a war between cartoonists and writers, with Worth trying to defend the cartoonists' understanding of visual creativity against the perception of a writer having said "Aha! A script! I knew writing had to be the secret of Disney’s success!" This speaks to the cartoonist’s fear that writers have no visual sense, and cannot imagine how stories could be created in picture form—and that therefore they wish to rewrite the history of animation. That a story synopsis will become their proof that the films were really written first, and only pictured later is a travesty that the cartoonist sees as greater by far than his own assumption that nothing was ever written.

But all of this misses the point—unlike live-action films the traditional animated cartoon, being made up of drawings, benefits from having its preproduction work shift into drawn mode as early as possible. Casting, set design, camera angle, etc., are all part of the same element—a drawing—and can evolve as the story does.

It would seem that story development at Disney’s was both collaborative and evolutionary. Initially ideas were developed in general story meetings, then drawn up as continuity sheets (a picture to show the set-up of each shot) along with a written description of each shot. This was then reviewed by Walt and, after revision, put into production. At least, it would seem to me that Walt and Ub had started working like that (with Ub doing the drawing up of what they had discussed) and that the process expanded from there.

By the '30s the process had grown to encourage the submission of gag ideas to hang on the basic plot outline. These would be pinned up on a board for discussion at the next story meeting. Such was the accumulation of sketches, which might be moved around to suggest a rough continuity of events, that it occurred to someone (Disney said it was Webb Smith) that it would save time doing the continuity sheets the same way—as moveable pinned-up drawings—rather than drawing up the results of one meeting on fixed pages, only to have to draw it all up again as the ideas changed at the next: the evolution of the storyboard.

(People still seem to miss the point that what was significant about the invention of the storyboard was not the fact that it laid out the film in pictures—the continuity sheets did that—but that it was flexible: it allowed the constant honing of ideas that Walt desired, the ability to edit until it all worked.)

Walt’s early staff were cartoonists. No writers, few artists, some only wannabe-cartoonists. But cartoons—as seen in the funny papers—used language. Cartoons weren’t just pictures, they told stories: the way they spoke—colloquially, often in dialect—was part of their character and fleshed out their performance. It was this element of performance that had led strip cartoonists to turn their hand to animation in the first place. It was performance that was at the heart of animation. Not drawing, that was just the means of expression: it was about entertainment, burlesque, hamming it up, putting on a show: performing. So cartoonists like words—as dialogue. Dialogue that is simplified, like the drawing, to have maximum effect with minimum effort. And they need words for explanation: a drawing may be worth a thousand words but an action might need a lot drawings—simpler to sketch the set-up and describe (briefly) the action.

Disney himself wrote copious letters and memos trying to communicate his ideas to others. Lead animators would be asked to prepare written character analysis of the cartoon stars they had help define, to inform the thinking of others handling those characters. Words, in short, are what we all use to communicate ideas—but very rarely does the average use of words in this way fall into the realms of "creative writing." It does not use language as imagery, merely as functional description. And that is how most of the written documents from the Disney studio come across—as functional descriptions of ideas. I think that this where the denial of "scripting" made by Disney and others comes from—that although the act of collating the results of a story meeting into a story (whether storyboarded or written) involves a lot of creative decision-making, reconciling of ideas and honing, and allows the opportunity to add ideas that occur along the way, it is ultimately about collating—and the process is very different from the perception of the Hollywood "writer," locked in a room with his typewriter churning out scene after finished scene by himself.

Writers, when they were introduced into the process, were expected to join in this free-for-all, contributory method (in which Walt was the final arbiter), and this was seen as very different from the sort of solitary authorship which writers were imagined to enjoy. What is notable is that this collaborative process was (I am led to believe) being used by writers—especially writers for radio comedy shows, where they were effectively creating the verbal equivalents of cartoons with word-play and funny voices in place of slapstick.

So yes, lots of writing went into concocting the storylines of Disney films—but it was the storyboards that were the prime tool, and that ended up as the final script. Simply because they were the easiest way to show what would be seen. Is any of the above contentious? Or does it just suggest that this "writing versus drawing" thing is just a red herring that distorts proper analysis of the Disney process?

MB replies: Although some of what Peter Hale says is unexceptionable, much of his message sounds to me like a subtler restatement of Worth's argument, and like Worth's, it simply doesn't square with the facts.

Storyboards didn't come into general use at the Disney studio until deep into the 1930s, and before they did (and even afterwards) story work typically began with the written word. David Gerstein offers many examples, I've offered some, and we both could offer many more. Those "continuity sheets" for cartoons like the Oswalds, the early Mickeys, and The Skeleton Dance were not story sketches but preliminary layouts prepared after the story had been written.

The usual Disney procedure was to employ outlines, treatments, and even scripts as launching pads, to give shape to ideas that were still too vague to be transformed into sketches. As work proceeded, drawings naturally and properly came to dominate. The people writing the stories were, almost to a man, cartoonists, so of course they were always thinking in cartoon terms and working their way toward translating their ideas into drawings. But any suggestion that the Disney studio's written documents existed mainly as a means of "collating" ideas that had already been expressed through drawings gets the process exactly backwards.

And I don't think it's useful to distinguish writers for animation and writers for live action on the basis of whether they worked in groups or in isolation. Many live-action writers collaborated with other writers, and many cartoon writers worked alone. What set live-action writers apart from cartoon writers was not how they worked, but how their minds worked.

[Posted December 18, 2009]

From Kirk Nachman: To err on the side of truth, or to err on the side of art? Scholars and historians vie the one, but art, so long associated with guile, may go the other way in artistically wanting times. The manure of a false historical premise may yet result in fine flowers. (Walt may have understood this better than any.)

Worth may be a, albeit indelicate, casuist, but he argues in favor of a philosophy of production, not posterity. Maybe he and his circle are not those to bring about a second Golden Age, yet there is something of a positivity in Worth's intentions that the generally negative practice of criticism and organizing the past cannot deny—The Creative.

It is nonetheless troubling to see such institutions (yourself and Worth's archive) so fractious and this side of slander, when the goal is a common one, and where the broad interest in preservation is left to a minority comprised mostly of yourselves, alone.

MB replies: If Worth and I have a common goal, I can't imagine what it might be. I don't see in what he says and does any genuine interest in "production" or "The Creative," as opposed to self-promotion and the glorification of his increasingly dysfunctional overlord.

[Posted December 19, 2009]

From Kirk Nachman: Your common goal: You are a long published biographer and historian, after-a-fashion, of Disney and animation history. Worth is a director of an actual facility (I won't debate abuses here, as they are hearsay, and we'll hang to jurisprudence to some degree) collecting artifacts from animation history. Your common interest and goals are thus entirely self evident, even if you evade or find the association distasteful, or have categorically forgotten what your masthead signifies.

Production and creativity: Worth is an exponent of Kricfalusi's approach to animation production, despite the difficulty the latter may have today in getting a cartoon produced (I don't make excuses for Kricfalusi's temperment, and it's clear he's alienated himself from his industry to great degree). But Kricfalusi is an artist, and a contributor to animation history quite actively by being part of animation history itself (not merely a scribe of the passing show). His creative contributions are undeniable. Worth is an instrument toward these ends.

MB replies: I think the root idea here is that Worth and John K. are entitled to my deference—my acknowledgment, explicit or otherwise, of their superior status—because Worth makes lots of computer scans of old children's books and John K. directed a few good cartoons late in the last century, and that my work as a biographer and historian, "after-a-fashion," shrivels by comparison with such towering contributions to the arts. No doubt there are people in today's animation industry, maybe quite a few of them, who would agree; and no doubt it's a symptom of my perversity that I persist in thinking otherwise.

[Posted December 20, 2009]

From Peter Hale: Let me make it clear I am not supporting Stephen Worth’s contention that "We don’t write our stories—we draw 'em" is to be taken to mean "We never write stuff down, we do it all in pictures." As David Gerstein pointed out, that is standard Disney simplification: the style of folksy hokum that Walt liked to use to "engage" his audience—the triumph of "entertainment" over "education": not just sugaring the pill, but refining the medicine to improve its taste rather than its efficacy. And yes, it falsifies the true picture. But how much? In what way?

Disney is not attempting to sell a lie here, but to exploit an angle—that the most visually interesting element of Disney animation, and the tool that sets them apart from live-action films (generally speaking, of the day) was the storyboard. As Michael says, storyboards came into use in the latter half of the '30s, but there has to have been an element of evolution—you don’t switch from OKing the final script, getting someone to draw up the shot-by-shot continuities, OKing them and assigning the scenes to the animators; to a system for discussing, reassessing, and editing the visual appearance of the whole short in one jump, surely? I feel it is reasonable to assume an ever-increasing use of gag drawings, inspirational sketches and the odd short scribbled sequence of comic-strip-style action was being made in the story meetings to illustrate the story development—"maybe we could use that gag here, after the sliding-down-the hill part." And some drawings are moved around to make the point.

From this practice the idea of using these pictures to build boards that could be used as the final continuity—not just one layout per shot but an illustration of the business within that shot—seems a more logical step. These early drawings of course, accrued IN RESPONSE TO THE WRITTEN SYNOPSIS previously circulated. (Excuse my shouting but I want it understood that I totally accept the point of initial written draughts—it would be self-defeating to ask for input on a synopsis that was presented as a drawn-up strip—the artist’s interpretation would limit the reader’s imagination and steer it into predictable channels. It would only allow for the refining of the core idea, which would become the function of the storyboard.

In the earlier Alice days the amount of time available for story writing must have been pretty tight. Maybe one intensive session kicking ideas around (possibly from a stock of themes accrued from those not used previously!) until a story was agreed (by Walt) and then roughed out as a shooting script. Now this is where it starts to become divisive. The result of the meeting, a detailed plot outline—"he does this, this happens, we see this..."—would be written down. (That is not to say nothing was drawn before this point, as it is commonplace for cartoonists to sketch an image that they can see as funny but can’t put into words, or a quick map to show how a set-up might work, but I agree that there need not be any drawing—this is two or three like-minded people with a common goal and a shared vision (cartoons like Aesop’s Fables) talking a film. Not a lot of room for lack of communication.

When it comes to the continuity sheets—the blueprints (at least in later Alices) for the production—I'm not inclined to see the dictation of shots written first and drawn up after as entirely realistic. I could more easily imagine someone roughing out the continuity from the final story description, then these being discussed and corrected before the written descriptions of these sketches and what they represent are prepared (one set-up per scene, so it needs to be explained) and the sketches drawn up in the continuity panels. This is because when you start to draw shots up you can find weaknesses that are not obvious in the written description—where a different shot, or combination of shots is necessary. I can't see Walt or Ub pursuing for long a system that did not take this on board. (It seems to me some continuity sheets have been traced off again for the animators—cheaper and easier than Photostatting—from the master sheet;is there anything to corroborate this as a usual practice?) Talking and writing it down; thinking (even doodling) and making notes.

My point is these films were collaboratively assembled under Walt’s lead—no idea was in until he had run with it and built it into his vision of the film. From this way of working eventually emerged the need (with the parting of Ub, who had been left to do his version of what Walt wanted while Walt worked on the Mickey stories with the newly recruited animators) to get more fresh ideas into the stories. Walt’s time was getting more widely spread, but he still had to approve the story, and in the '30s this still meant his inhabiting the films—shaping what he was hearing to his ideal. Hence more delegation of story work, and the circulating of synopses to hook in more ideas. Again—LOTS OF WRITTEN WORK. Mood, character, motive—all discussed with words (you can sketch mood, but first you must agree what mood; you can draw the various aspects of a character’s personality, but first you must agree what these aspects should be; and it is a waste of time drawing all the aspects of a character’s back history in order to discuss what his motives might be.) But when you have got your storyline it becomes more and more advantageous to explore the visual elements you will employ.

How sterile to prepare a story in great detail and only then consider how it will be drawn. How much more useful to have visuals to point the way, to bounce off, to stimulate new ideas of what might happen. This Walt pursued, and the end result was the storyboard: where the film could be "made" as completely as possible to Walt’s satisfaction, for everyone to follow, before the far greater investment of time and money that was the production process was set on its juggernaut path. This was why the storyboard was so important. The mythology of its being the sole process grew, I think, out of the usefulness of, and thus reliance on, the storyboard as consulting document. According to Wilfred Jackson, Snow White (the studio’s biggest gamble) was the peak of Walt’s obsessive desire for getting as much input, as much analysis and as much discussion—in short as much collaboration—as possible into the story process.

Subsequently story production got increasingly streamlined—smaller teams, smaller meetings—with fewer people involved until the storyboard stage. This—along with the fact the the studio loved to tout their magical "storyboard" process as a point of difference, and thus interest, for writers of film magazines—led to people in the studio accepting the storyboard as all important. But it would not have evolved, endured, or emigrated to other studios if it was not of intrinsic importance. And that importance was a) the ability to share the vision of the finished film by the people who needed to know how it was supposed to look; and b) the ability to keep changing the way it looked until it seemed to be working at its best.

The storyboard is more than script, it is the tryout for set design, lighting, casting, make-up, and above all direction and cinematography. And then it can be shot on film and played back with soundtracks—test and finished animation can gradually be added to continually monitor the progress of the film…all to give Walt the assurance that it was still working And ultimately this is why I can’t see this writing versus drawing thing as very important. What made most of Disney’s films succeed was his involvement. As he let go of the reins on productions so the overall restless search for "better" seemed to disappear. Some people were able to pursue new stylistic ideas that Walt had frowned on, but the sincerity became faked. Without his obsessive scrutiny, neither storyboard nor script was delivering what it could have.

MB replies: As to the evolution of the storyboard, and of story work at Disney's in general, I've written in detail about those subjects in both Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age and The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. I won't repeat myself here, except to emphasize what Wilfred Jackson once told me, that in the early '30s especially there simply wasn't a fixed procedure for making a Disney cartoon; there was instead constant change. That change led, over time, to a greater reliance on the storyboard, for reasons that Peter Hale suggests. And I certainly agree that Walt Disney's own diminishing involvement in the animated films that bore his name led to a steady decline in the quality of those films.

[Posted December 23, 2009]

From Kirk Nachman: It is not my purpose to denigrate your efforts nor aggrandize Kricfalusi and Worth, although it may appear I've done just that. I use the term "after-a-fashion" solely because popular histories aren't quite like good old academic histories. I do find your reductions of the two amusing. I suppose I could likewise reduce you to a fanzine scribbler, and an arrogating, pompous-ass.

However, I'll never make the mistake that "archivists" and "historians" have anything in common. Or that "archivists" who argue in favor of a specific creative process have anything to do with creativity, or that contributors to the history of an art-form have any place in that history unless certain intelligentsia give their assent.

[Posted December 28, 2009]