"What's New" Archives: September 2008

September 26, 2008:

September 25, 2008:

September 23, 2008:

September 22, 2008:

September 26, 2008:

More on Ken O'Connor

Darrell Van Citters, whom I mentioned yesterday in my item about Ken O'Connor's rebuffs of my efforts to interview him, wrote to me today about O'Connor as Darrell knew him at CalArts:

Just to set your mind at ease, Ken didn’t go around speaking ill of you. The only time it ever came up was when I mentioned it in connection with having you interview him. It was really too bad that he chose to shut down. He had a lot to say about his art, working in a commercial world, the Disney studio and certainly studio history.

I'm sorry O'Connor didn't agree to an interview. I would have enjoyed talking with him, as I enjoyed talking with Ben Sharpsteen, Ward Kimball, and so many others among the people O'Connor worked with at the Disney studio.

September 25, 2008:

Can You Top This Dept.

Last summer, my friends Jerry Beck and Amid Amidi, over at Cartoon Brew, posted some vintage photos of Jerry and Will Friedwald with such legendary figures as Bob Clampett and Friz Freleng. Not to be outdone, I herewith offer an even older photo of even older people.

Last summer, my friends Jerry Beck and Amid Amidi, over at Cartoon Brew, posted some vintage photos of Jerry and Will Friedwald with such legendary figures as Bob Clampett and Friz Freleng. Not to be outdone, I herewith offer an even older photo of even older people.

This is me in January 1976 (in what I've come to think of as my Tony Orlando Period), with John Randolph Bray, who was then 96 years old. If you're familiar at all with animation history,the Bray name will ring a loud bell: he started producing cartoons around 1912, most famously the "Colonel Heeza Liar" series, secured patents on many basic animation processes, and collected royalties from people like Walt Disney as late as the early '30s. He was living in Norwalk, Connecticut, when I interviewed him; John Canemaker, who had already interviewed him for Filmmakers Newsletter in 1974, put me in touch.

The interview was a washout, alas, but I valued the opportunity to meet someone who was a participant in American theatrical animation almost from its inception. I can't think of anyone else I ever interviewed who went back as far in cartoon antiquity, except for Winsor McCay's assistant, John Fitzsimmons, whom I interviewed two years later.

On my foray into Connecticut—John Benson and Bill Peckmann drove me there from New York City —I also interviewed Preston Blair (who was considerably livelier than J. R. Bray). The next day, a Sunday, Michael Sporn and Maxine Fisher picked me up in Manhattan and we drove to New Jersey for an interview with Otto Messmer, another veteran of silent-cartoon days ("Felix the Cat"). A productive trip, and the sort of thing that was almost too easy to arrange in those days, when hundreds of veterans of the "golden age" were still active and happy to talk about their work.

On my foray into Connecticut—John Benson and Bill Peckmann drove me there from New York City —I also interviewed Preston Blair (who was considerably livelier than J. R. Bray). The next day, a Sunday, Michael Sporn and Maxine Fisher picked me up in Manhattan and we drove to New Jersey for an interview with Otto Messmer, another veteran of silent-cartoon days ("Felix the Cat"). A productive trip, and the sort of thing that was almost too easy to arrange in those days, when hundreds of veterans of the "golden age" were still active and happy to talk about their work.

Bill Peckmann took the Bray photo, I think. I have very few such photos of me with the animation people I interviewed, and even fewer good ones. I relied for too long on cheap, inadequate cameras when better ones seemed beyond my means. As I'm reminded when I look through my photos, cheap cameras are no bargain.

I finally bought a decent 35mm camera when Phyllis and I made a January 1979 trip to California to gather illustrations for my ill-fated Warner Bros. art book, but it was damaged when we flew from San Francisco to Los Angeles. As a result, I have no pictures from that trip except for a few from northern California: a couple of shots of Ed and Alice Benedict, and the accompanying photo of Phyllis with Ben Sharpsteen, outside the museum at Calistoga, in the Napa Valley, that bears Ben's name and that had just been completed when we saw it.

Which Reminds Me...

I was impressed by the Sharpsteen Museum when I saw it in 1979, and I was impressed again when we re-visited it in June 2002; you can get a good idea of what it's like by visiting the museum's Web site. The museum now includes a founders' room devoted to Ben and Bernice Sharpsteen, and that room's exhibits include memorabilia of interest to Disney fans. A monograph on Ben's life is for sale at the museum store for $8.50.

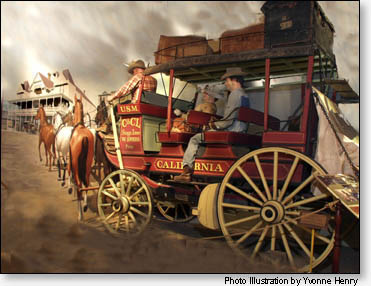

There's a sort of Disney touch evident in some of the exhibits, like the highly detailed diorama that depicts Calistoga at its beginnings, as a hot springs resort in the 1860s. And then there's a restored stagecoach that has been incorporated ingeniously into a painted background, so that the stagecoach appears to be approaching the Calistoga Hotel (see the accompanying illustration from the museum's Web site). That painted background is the work of Kendall O'Connor, a leading Disney layout artist who worked with Ben Sharpsteen on shorts like Clock Cleaners in the '30s and later with Ward Kimball on the Tomorrowland TV shows. He was recruited by Ben to help with the museum.

I never met Ken O'Connor, but I had some strange encounters with him even so, via the mail and Ben Sharpsteen himself. I wrote to O'Connor in 1976, seeking to interview him for my book Hollywood Cartoons when I visited California that fall and sending him a copy of Funnyworld—I think No. 14, which had a cover feature on Ralph Bakshi and Fritz the Cat—as an example of my work. I got back a brusque reply: "I'd rather not appear in a periodical that would devote so much space to promoting a character such as Bakshi."

I never met Ken O'Connor, but I had some strange encounters with him even so, via the mail and Ben Sharpsteen himself. I wrote to O'Connor in 1976, seeking to interview him for my book Hollywood Cartoons when I visited California that fall and sending him a copy of Funnyworld—I think No. 14, which had a cover feature on Ralph Bakshi and Fritz the Cat—as an example of my work. I got back a brusque reply: "I'd rather not appear in a periodical that would devote so much space to promoting a character such as Bakshi."

I met and interviewed Ben Sharpsteen on that 1976 trip, with Milt Gray and Don Peri in attendance. After I returned home, I wrote to O'Connor again, renewing my request for an interview and telling him that I had made a mistake by taking Bakshi seriously and that I had no interest in "promoting" him. I received no reply.

In 1977, when I learned from Don Peri that O'Connor was coming to Calistoga to work on museum exhibits, I wrote to Ben asking him to put in a good word for me. Here's my note from my phone conversation with Ben soon afterwards: "Ken O'Connor - still refuses to cooperate, saying he doesn't want to be associated with Bakshi, maker of 'pornographic' films."

That was enough for me. Darrell Van Citters, then a third-year student at CalArts, wrote to me in 1978, asking me to try again to interview O'Connor, who was teaching layout and perspective at that school. "It seems Ken has no respect for Ralph Bakshi and disagreed strongly with your reviews and analyses in Funnyworlds 14 & 15 of Ralph's work," Darrell wrote. As I told Darrell in my reply, I had run out of cheeks to turn, and I wouldn't write to O'Connor again.

And I didn't. Perhaps I should have, if only in the faint hope of forestalling some of the negative comments about me that O'Connor was evidently all too eager to spread. Who knows how many of his CalArts students came away from his classes believing that I was Al Goldstein or Larry Flynt in disguise?

September 23, 2008:

Elias Disney in His Own Words

There'll be a lot of Disney-related stuff here for the next few weeks. If you'd rather read about other people and other studios, please bear with me. Walt was simply more interesting than almost anyone else who falls within this site's purview, and I can't resist sharing some of the things that have come into my hands.

There'll be a lot of Disney-related stuff here for the next few weeks. If you'd rather read about other people and other studios, please bear with me. Walt was simply more interesting than almost anyone else who falls within this site's purview, and I can't resist sharing some of the things that have come into my hands.

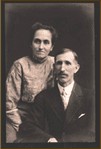

To begin: When I was working on The Animated Man: A Biography of Walt Disney, I tried with mixed success to track down copies of a number of primary sources, including a brief family history written by Walt's father, Elias Disney, who is pictured at right with his wife, Flora (Bob Thomas mentions the essay, and gives its date as 1939, on pages 7-8 of his biography of Roy O. Disney). I couldn't find a copy of Elias's essay then, but now I have: it's reproduced within a 1975 newspaper article on file at the Huron County Museum in Goderich, Ontario, which I visited earler this month. I've posted the complete Elias Disney essay under my Essays tab, and you can read it by clicking on this link.

I like Elias's courtly, old-fashioned prose in what he titled his "Biography of the Disney Family in Canada." For that matter, I came away from writing The Animated Man liking Elias himself. He gets a bad rap in Neal Gabler's Disney biography —the first sentence in the first chapter is "Elias Disney was a hard man"—but that's simply evidence of Gabler's ridiculously narrow sympathies. I don't think a "hard man" could have won the unforced affection for his father that Walt showed repeatedly in his 1956 interviews with Pete Martin, and that his brother Roy showed in his interviews with Richard Hubler, soon after Walt's death. Elias may have been difficult at times, but he was, I have no doubt, a good man and a loving father.

September 22, 2008:

Goderich and Man

I'm back, after a very long driving trip that took Phyllis and me up the East Coast and into Canada's Atlantic provinces. We then drove to Quebec City and through Ontario, until we crossed into Michigan and headed home—arriving just in time to have our lights knocked out for two days by Hurricane Ike. We passed within hailing distance of Ottawa, but exactly one week too early to attend the Ottawa International Animation Festival. Other commitments along our route dictated our schedule, but I regret missing this year's event.

By way of consolation, I did persuade Phyllis to make a detour through the ancestral Disney lands in southwestern Ontario. She would have preferred to go home by way of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, but I persuaded her that an overnight stay at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival might be a satisfactory alternative. It wasn't, really; lodging in Stratford is wildly overpriced, and we saw a well-staged but badly acted performance of Hamlet. The next day we drove northwest through tiny Bluevale, near where Walt's father, Elias, was born, and then southwest to spend a few hours in Goderich, Huron County's seat and the site of Central School, which Elias attended. That's the school building I'm looking at in the photo just above. It's a remarkably handsome structure to have been built in 1856, in what was then a barely tamed corner of a huge, wild country.

The school is now part of the Huron County Museum, and Patricia Hamilton, the curator, and her colleagues kindly made available copies of their material on the Disneys' associations with the area. I didn't go looking for the locations of the Disney farms, although I was told that one Disney house is still standing. I was most curious about what that part of Ontario looks like, and it fulfilled my expectations: neat, prosperous-looking farm country, its roads laid out in a grid, with little in the way of hills or other distinguishing topographical features. (See the photo below for a typical farm.)

The school is now part of the Huron County Museum, and Patricia Hamilton, the curator, and her colleagues kindly made available copies of their material on the Disneys' associations with the area. I didn't go looking for the locations of the Disney farms, although I was told that one Disney house is still standing. I was most curious about what that part of Ontario looks like, and it fulfilled my expectations: neat, prosperous-looking farm country, its roads laid out in a grid, with little in the way of hills or other distinguishing topographical features. (See the photo below for a typical farm.)

The area was no doubt a lot rougher-looking when the Disneys settled there, more than 150 years ago, but probably the shape of its future was visible even then. So thoroughly civilized is Huron County now that Goderich bills itself as "the prettiest town in Canada." While that boast may be open to challenge, it has a lovely lakefront—on Lake Huron—and at least one superb restaurant, Thyme on 21 (the number of the main highway through town).

I wanted to visit the Bluevale-Goderich area when I was writing The Animated Man, but such a visit was never at the top of my list of priorities, simply because what happened there seemed so remote from Walt himself. Elias Disney left Canada almost twenty-five years before Walt was born, and Walt may not have visited western Ontario for the first time until the 1950s. I've had trouble pinning down the date of his first visit, although his daughter Diane Disney Miller thinks it was early in that decade. Goderich's downtown is laid out in a hub-and-spoke pattern, and Diane wonders if that might have influenced the layout of Disneyland. Interesting thought; maybe Goderich wasn't so remote from Walt's own life after all. In any case, now I've been to Goderich, and I'm very glad to have made the visit.

Banned in Burbank!

As I've mentioned in earlier posts, The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney has been for sale at some of the Walt Disney Company's own retail stores, at Walt Disney World, on Fifth Avenue in New York, and at the Disney studio itself. But no more.

As I've mentioned in earlier posts, The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney has been for sale at some of the Walt Disney Company's own retail stores, at Walt Disney World, on Fifth Avenue in New York, and at the Disney studio itself. But no more.

While I was away, I received an email message from my editor at University of California Press. She told me that the Disney stores had started selling the book "before there was an 'official' review by the Disney lawyers of the book—apparently they do this for all books they carry." When the lawyers finally looked at The Animated Man, they decided that it didn't meet their criteria, whatever those are. As a result the Disney stores will no longer carry the book, even though it sold well enough at the stores to generate reorders.

My editor believes "there is no reason to worry about getting sued or harassed." I agree. As some of my detractors never cease pointing out, I have a law degree (from the University of Chicago), and even though I've never really practiced law, I'm alert to the legal ramifications of what I write. There are no legal clouds over The Animated Man. My book has been barred from the Disney stores for other reasons, and it's not hard to guess what they might be.

As Diane Disney Miller observed tartly when I told her what the Disney lawyers had done, the Disney stores will continue to carry Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. That book depicts Walt Disney, inaccurately, as a haunted, tormented wretch, and it is otherwise packed with errors and distortions. But Gabler enjoyed the company's blessing and cooperation during the research, writing, and promotion of his book; I did not. Probably that's all that matters to the Disney lawyers, and to their superiors as well.

And speaking of bad books...

Diane Miller called my attention to a New York Times review of Marc Eliot's latest book, on Ronald Reagan's Hollywood years. Eliot is, of course, also the author of a Disney biography unparalleled for sheer awfulness. That book alone is reason not to take him seriously as a writer, but somehow each new book of his winds up getting respectful attention from reviewers who should know better. Janet Maslin, the Times's reviewer, circles around Eliot's usual offenses as she reviews Reagan: The Hollywood Years, but she can't bring herself to slam the nasty thing shut and aim it at a trash can:

Mr. Eliot deals erratically, even perplexingly, with the job he has taken on. He cannot easily reconcile cheap shots about Reagan’s sorriest film roles with a tough look at Reagan’s most serious Hollywood job: serving as president of the Screen Actors Guild during some of that union’s rockiest times. He does a shockingly sloppy job of annotating important research, even though his deep immersion in that research is unmistakable. He winds up with an intriguing but uneven book, representing a largely squandered opportunity.

Print outlets for book reviews are rapidly shrinking in number. What's saddest in these circumstances is not that so many good books are getting so little attention, but that so many flagrantly bad ones, like Marc Eliot's, are getting far more attention than they deserve.