"What's New" Archives: July 2007

July 29, 2007:

July 25, 2007:

July 24, 2007:

July 23, 2007:

July 18, 2007:

July 12, 2007:

July 11, 2007:

July 6, 2007:

July 3,2007:

July 1, 2007:

July 29, 2007:

Odds 'n Ends

° From Bill Benzon, a link to a most interesting piece by Art De Vany on the perils of economic forecasting in the movie business. De Vany wrote his piece about Treasure Planet, toward the end of 2002, but what he says is relevant today, when Ratatouille seems to be staggering a bit under the weight of unrealistic expectations and the overpowering performance of The Simpsons Movie. De Vany wrote his piece as a Los Angeles Times op-ed, but it was rejected, and he resurrected it on his blog early this year, under the title "Seeing Things at Disney Before They Got Rid of Eisner." Highly recommended.

° Also from Bill Benzon, a typically pertinent response to my July 25 comments on Brad Bird's The Iron Giant. You can read Bill's comments, and my response, by going to the feedback page for that film.

° Speaking of Ratatouille, the Disney fan site LaughingPlace.com has published a substantial excerpt from an interview by Rhett Wickham with Mark Walsh, one of the film's supervising animators. Lamentably, the Pixar people have been mostly anonymous, apart from the front-line folks like Bird, John Lasseter, Pete Docter, and Andrew Stanton. It's good to see one of them take the spotlight. The complete interview is in print in the tenth issue of LaughingPlace.com's quarterly magazine, Tales from the Laughing Place. I must confess I haven't yet seen a copy of the magazine. Its contents seem to be devoted largely to recent developments at the Disney theme parks, which are of less interest to me than Disney history. But the magazine appears to be a solidly professional product, and certainly Rhett Wickham's interview suggests that I need to make up for lost time by picking up a few back issues. You can order back issues, or a subscription, by clicking on this link. And you can learn more about the magazine itself by clicking here.

Woody Revisited

I haven't yet watched any of the cartoons in the new Woody Woodpecker DVD set, but Gene Schiller's comments make me wonder if the set—very well put together, from most reports—might stimulate a re-evaluation of the Lantz cartoons, in the way that revivals of other kinds have stimulated re-evaluations of neglected authors and artists and filmmakers. Gene writes:

Why such faint praise for the Walter Lantz collection? In particular, I find Woody refreshing, with none of the superciliousness of Bugs, or Daffy’s insecurity. At his best, he’s a latter day Till Eulenspiegel—a pure comic anarchist. What’s not to like? I think some of the Lundy cartoons (Wild and Woody and Woody the Giant Killer) are worthy of re-evaluation. Culhane has some great moments (the final frames from The Dippy Diplomat and that daffy song in Ski for Two) but, The Barber of Seville. doesn’t work for me at all. It’s well-timed, but like a lot of his stuff, not terribly funny.

I've always felt much the same way about The Barber of Seville, which I think has benefited inordinately over the years from praise by Shamus Culhane's journalist cousin John. (Ditto for the Dwarfs' march home from the mine in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.) I remember hearing Shamus and John gab about Barber's "jump cuts" at the American Film Institute Theater at Kennedy Center, many years ago; I'm still not sure what they were talking about.

July 25, 2007:

Sporn on DVD

First Run Features has released two modestly priced ($12.99 at amazon.com) DVDs of films by Michael Sporn, each containing two of the adaptations of Hans Christian Andersen stories that Sporn made for HBO between 1989 and 1992. First Run released four other Sporn films on DVD in 2003; you can read my review by clicking here.

Sporn films are otherwise not plentiful on DVD; some of his best efforts, adaptations of children's books for Weston Woods, are for all practical purposes limited to the educational market. But at least the Oscar-nominated Doctor DeSoto (1984) and the haunting Man Who Walked Between the Towers (2005) are available on a couple of Scholastic DVDs, also for $12.99 each.

Three of the films on the new First Run DVDs are astonishingly beautiful (I except only The Emperor's New Clothes), and they're beautiful in very different ways. Nightingale, for example (based on Andersen's The Emperor's Nightingale) is Japanese in design, echoing not just classic screens but, in the appearance of the characters, contemporary manga and anime. The Little Match Girl, set in Manhattan, feels, in the way it looks and in its dry tone, like New Yorker cartoons and illustrations come to life (with maybe a touch of John Stanley's Little Lulu, too). There's nothing in the least self-conscious about this adaptation of such varied styles; Sporn simply uses whatever best suits his purposes in a given film.

Three of the films on the new First Run DVDs are astonishingly beautiful (I except only The Emperor's New Clothes), and they're beautiful in very different ways. Nightingale, for example (based on Andersen's The Emperor's Nightingale) is Japanese in design, echoing not just classic screens but, in the appearance of the characters, contemporary manga and anime. The Little Match Girl, set in Manhattan, feels, in the way it looks and in its dry tone, like New Yorker cartoons and illustrations come to life (with maybe a touch of John Stanley's Little Lulu, too). There's nothing in the least self-conscious about this adaptation of such varied styles; Sporn simply uses whatever best suits his purposes in a given film.

Mark Mayerson, in typically trenchant comments about the new DVDs, remarks on how Michael is able to make films that are unmistakably "Michael Sporn films" even when beset by a client's demands (HBO insisted that he change the narrator for Little Match Girl, from Gilbert Gottfried to F. Murray Abraham), and even though he gives his animators a great deal of freedom. "I'm not sure how he manages to pull this off," Mayerson writes, "though I think that his taste is at least partly responsible. Somehow, when he's making creative choices or selecting a crew, his decisions invariably work (though Mike would be first one to lament the compromises he's been forced to make)."

I'd point, too, to some salient characteristics of Michael's work that as far as I know have always survived any meddling clients or headstrong animators. One is the stylistic unity he achieves between his hand-drawn characters and his hand-drawn backgrounds (here the influence of his mentor and idol, John Hubley, is very much evident). Another is the uncanny way that he makes each of his characters distinct and memorable, even when—and this is often the case, given his budgets—he is working with very spare designs and limited animation. His choice of voices accounts for some of this, I'm sure; the voices for his films, by leading Broadway and Hollywood actors, are almost always excellent, obviously chosen not for their name value but for what they can bring to a character, or a narration. (As good as F. Murray Abraham is, Michael was right to want Gilbert Gottfried.) It's surely in his direction of his voice actors, and of his animators, that Michael does the work—the exercise of his good taste, as Mark Mayerson suggests—most important to this result.

I'd point, too, to some salient characteristics of Michael's work that as far as I know have always survived any meddling clients or headstrong animators. One is the stylistic unity he achieves between his hand-drawn characters and his hand-drawn backgrounds (here the influence of his mentor and idol, John Hubley, is very much evident). Another is the uncanny way that he makes each of his characters distinct and memorable, even when—and this is often the case, given his budgets—he is working with very spare designs and limited animation. His choice of voices accounts for some of this, I'm sure; the voices for his films, by leading Broadway and Hollywood actors, are almost always excellent, obviously chosen not for their name value but for what they can bring to a character, or a narration. (As good as F. Murray Abraham is, Michael was right to want Gilbert Gottfried.) It's surely in his direction of his voice actors, and of his animators, that Michael does the work—the exercise of his good taste, as Mark Mayerson suggests—most important to this result.

The HBO films are by no means perfect, the basic problem lying with Andersen's stories themselves, which are not only morbid at their core but also resist expansion to the length required to fill a half-hour TV slot. There's no faulting Maxine Fisher's writing, but she had an overwhelming task. Only The Little Match Girl is really successful as a cartoon story—it departs radically from Andersen's original—but The Red Shoes and Nightingale are gorgeous enough to diminish the importance of story problems.

Michael Sporn is now embarked on a feature-length film based on Edgar Allen Poe's life and work—made on a shoestring, as usual. (Click here to go to a work-in-progress page on the film, part of Michael's lively and interesting Web site.) When I last wrote about Michael's films, early in 2004, I said this: " I wonder sometimes what would happen if Michael finally had adequate budgets and could escape the madness that lets a Ralph Bakshi or a Don Bluth command millions while a Michael Sporn scratches for thousands. Would bigger and better films result, or would the inventiveness now demanded by his circumstances diminish? I'd certainly like to find out."

I still would, but I guess I'll have to wait a while longer. In the meantime, I'm looking forward to seeing Poe.

The Iron Giant Revisited

Speaking of Mark Mayerson, as I was in the preceding item, I found his recent post on Brad Bird's films exceptionally interesting, since I read it just after watching Bird's first feature, The Iron Giant, again (the "special edition" DVD, with Bird's audio commentary). I really wanted to like The Iron Giant this time, since I didn't like it when I saw it in a theater in 1999—you can read my thoughts about it here—and I have been told repeatedly what an idiot I am for not appreciating such a masterpiece.

Speaking of Mark Mayerson, as I was in the preceding item, I found his recent post on Brad Bird's films exceptionally interesting, since I read it just after watching Bird's first feature, The Iron Giant, again (the "special edition" DVD, with Bird's audio commentary). I really wanted to like The Iron Giant this time, since I didn't like it when I saw it in a theater in 1999—you can read my thoughts about it here—and I have been told repeatedly what an idiot I am for not appreciating such a masterpiece.

Unfortunately, I'm still an idiot. As brilliant as Iron Giant is in some ways, especially its integration of hand-drawn and computer animation, it suffers from what is, for me, a crippling flaw.

Mark Mayerson identifies a concern with persecution of the talented as a theme in all three of Bird's feature films, including The Incredibles and Ratatouille. "Bird appears to feel that talent should rise to the top and that others should willingly defer to talent," he writes. "This is where the charges of elitism, and even fascism, are leveled at Bird." Bird is a gifted artist whose own immense talent went insufficiently recognized for too long, and who had to wait until middle age—he will turn 50 on September 11—to direct his first feature.

I found Bird's preoccupation with talent's entitlements a troubling but minor aspect of The Incredibles, and I don't think it's a major factor in Ratatouille, either. In The Iron Giant, though, I feel his concern for the talented spilling over into something dismayingly close to self-pity.

The Iron Giant is set in 1957, at the time of Sputnik (which went up a few weeks after Bird's birth), and of what Bird obviously believes was unjustified cold-war paranoia. Mr. Incredible and Remy the rat must overcome a climate of hostility, to be sure, in addition to individual opponents, but they don't have to deal with anything as threatening as the national hysteria and the deranged government agent that menace the giant and his puny human protector. If the people persecuting your heroes are homicidal madmen, there's no need to give any serious thought to their motives. You can instead wallow in the injustice of it all; and in The Iron Giant, that's essentially what Bird does.

I still think it's a shame that Bird didn't set The Iron Giant in our own time, not least because making it a contemporary story, like The Incredibles and Ratatouille, might have served as a check on his own most unfortunate tendencies. But he didn't, and so I have no choice but to go on being an idiot.

July 24, 2007:

O'Brian, Not Winchell

Michael Sporn writes about my July 23 item on Dave Hilberman:

That's a very interesting post about Hilberman. Thanks for setting the record straight. I've recently read about the "Walter Winchell" column in several accounts of Hilberman's story. However, Jim Logan, who was working at Tempo at the time, told me that Jack O'Brian in the Hearst papers—the Journal American in NYC—wrote a full column on the communists operating Tempo. This was definitely something O'Brian would have written. My father was an ardent reader of the paper and swore by O'Brian's nasty gossip column. Winchell's column was syndicated but not in the Hearst papers, so it's unlikely that Logan would have confused the two. It also makes sense that an article appeared in Counter-Attack, as you wrote, and was then picked up by O'Brian or Winchell or whoever.

Counter-Attack was evidently a conduit for anti-communist dirt that J. Edgar Hoover's FBI wanted to spread around. When I used the Freedom of Information Act to get a copy of part of the FBI's file on UPA, that file included a 1950 issue of Counter-Attack that slammed UPA using information that almost certainly originated with the FBI—that was, in fact, part of the same file.

July 23, 2007:

Hilberman, Disney, and HUAC

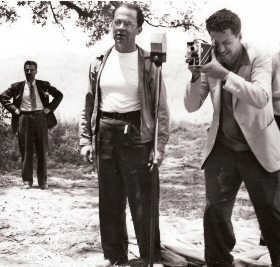

Dave Hilberman, a major figure in Hollywood animation's history by virtue of his leading roles in the 1941 Disney strike and in the founding of the UPA studio a few years later, died July 5, at the age of 95. That's Hilberman in the center of the photo, which was taken by Don Christensen during the strike; the shutterbug at Hilberman's left is another important striker, John Hubley. I hope to get around to posting one or both of my interviews with Hilberman soon, and I'll have more to say about him then, but after reading his obituary in the Los Angeles Times, I think a few words may be in order now.

Dave Hilberman, a major figure in Hollywood animation's history by virtue of his leading roles in the 1941 Disney strike and in the founding of the UPA studio a few years later, died July 5, at the age of 95. That's Hilberman in the center of the photo, which was taken by Don Christensen during the strike; the shutterbug at Hilberman's left is another important striker, John Hubley. I hope to get around to posting one or both of my interviews with Hilberman soon, and I'll have more to say about him then, but after reading his obituary in the Los Angeles Times, I think a few words may be in order now.

That obituary, by Charles Solomon, gets off on the wrong foot in its lead paragraph, which says that Hilberman's "union activities at Walt Disney Studios and brief membership in the Communist Party led to his blacklisting..." For one thing, Hilberman's party membership was not exactly "brief."

Solomon quotes a 1979 interview in which Hilberman told John Canemaker that "Up to the war, for about three years, I was a communist. Once the war came along, everybody plunged into the war effort, everybody's on the same side." Hilberman joined the party in 1935. I asked him in 1986, in my second interview, if he left the party as a result of the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1940. He said he did not but instead remained a communist for several years after that, until "probably '44 ... to '44-'45."

That in itself was revealing. Many idealistic people joined the Communist Party in the 1930s but left disillusioned after the grotesque Moscow show trials or after Stalin and Hitler signed the 1940 non-aggression pact. To have joined in the mid-1930s and remained a member for almost ten years was evidence in itself of a strong attachment to the party.

A larger problem with Hilberman's account, I learned much later, was that the U.S. Communist Party ceased to exist on May 20, 1944, the year Hilberman said he "probably" left it. The party transformed itself into a "political association" at the behest of Earl Browder, its general secretary, but reconstituted itself as a party in July 1945 (and expelled Browder a few months later). At the least, Hilberman was being disingenuous when he told me he left the party in 1944, because there was for much of that year no party to be a member of. I don't know if he was a communist after the party came back into existence.

However questionable Hilberman's account of his party membership, I'm sure we can trust what what he said about the consequences of Walt Disney's 1947 testimony about him before the House Un-American Activities Committee. In that testimony, Walt attacked Hilberman and accused him (accurately, of course) of being a communist. Solomon's obituary says that "Disney's testimony and a comment by gossip columnist Walter Winchell that Hilberman was a communist forced the closure of Tempo Productions," the New York commercial studio of which Hilberman was co-owner with Bill Pomerance.

That is incorrect. Hilberman himself told me in 1976 that Disney's testimony "had no impact" in 1947 because Tempo had just gone into business (see page 201 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney). "We were able to grow without that affecting us at all," he said. It was not until late in 1953—more than six years after Walt's testimony—that the roof fell in. Tempo went out of business in 1954, and Hilberman himself was blacklisted.

The trigger was not what Walt Disney said but an exposé of Hilberman and Tempo in the December 25, 1953, issue of a Red-baiting rag called Counter-Attack. That publication cited the testimony of a number of HUAC witnesses, including Walt, but it's misleading, at best, to suggest that Tempo's collapse in 1954 was caused by what Walt said in 1947. It's even more of a stretch to connect Hilberman's blacklisting with his 1941 union activities, as Solomon does in his lead paragraph. I know of nothing to suggest that Walt pursued Hilberman vindictively in later years, however much he disliked him for his role as a strike leader.

In sum, Walt Disney was less an avenger than Solomon's obituary suggests, and Dave Hilberman more of a communist.

The attacks on Hilberman are usually described as a "smear," as if there were no truth, or only a smidgen of truth, in the accusations that he was a communist; but the accusations were true. So, does that mean Walt was justified in denouncing Hilberman before HUAC, or that the blacklisting of Hilberman was in any way acceptable? Not at all. Dave Hilberman was a communist, but there was never anything "subversive" about him, unless you count his unconventional political beliefs; and like every other American, he was entitled to believe what he pleased. It's because HUAC and its supporters—including, unfortunately, Walt Disney—chose to disregard that bedrock principle that their actions are so widely and justifiably criticized today.

July 18, 2007:

Walt's Desert Hideaway

Two years ago, when I was deep in research for The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, I spent a day at Palm Springs, California, much of it at Smoke Tree Ranch, where Walt and Lillian Disney built two vacation homes. The picture above is of Smoke Tree's bowling green, one of the settings for Walt's late-life passion, lawn bowling.

Now you too can visit Smoke Tree, and without ever leaving your air-conditioned home (an important consideration—Palm Springs' desert warmth is delightful in the winter, but the town is hot in the summer). A new DVD, Smoke Tree Ranch, A Way of Life, is a loving tribute to the ranch and some of its famous residents and guests, including Dwight Eisenhower and, of course, Walt Disney.

The DVD has no footage of Walt at play, unfortunately, although it does include a dozen or so photos of him, some of them new to me; and there's good 16mm footage of other lawn bowlers in action. No doubt the DVD is sugar-coated in some respects—there's no reference to the exclusionary policies, based on race and religion, that were commonplace when Smoke Tree came into existence in 1930—but its portrait of a thoroughly pleasant (and highly privileged) way of life rings true.

The only on-camera interview is with Frank Bogert, a former mayor of Palm Springs now well into his nineties. Bogert became acquainted with Walt when they rode together in the 1930s (an association documented in contemporary newspaper stories). I interviewed Bogert by telephone for The Animated Man; he's quoted on pages 134-35. I had a good time talking with him, and he's no less enjoyable on the DVD.

There's no time specified on the DVD, alas, and I couldn't get the disc to divulge a total time; but my recollection is that the film runs well over an hour, not counting some extras of limited interest.

You can buy the DVD from the good people at the Palm Springs Historical Society (another place I enjoyed visiting in 2005). Send a check for $34.66 ($29.95 for the DVD, plus $2.32 sales tax and $2.39 for postage) to Palm Springs Historical Society, P.O. Box 1498, Palm Springs CA 92263. Or you can fax credit-card info for that amount to 760-320-2561.

And if you'd like to learn more about Smoke Tree Ranch but the DVD's price seems a little steep, you can always go to Smoke Tree's Web site.

July 12, 2007:

Missing Footage in Dumbo?

Mac Carlson calls my attention to a 2006 review of the most recent incarnation of the Dumbo DVD in which the author, Glenn Erickson ("DVD Savant"), says in a footnote:

A mystery that's bothered Savant since 1972, when UCLA associate professor Bob Epstein showed us an original print of Dumbo at UCLA: Epstein said that the show was originally a couple of minutes longer. The crows appeared once or twice earlier to serve as a mocking chorus, commenting on the dowager elephants and the pitiful Dumbo. Looking at the film with this in mind we see plenty of abrupt blackouts and music cuts to make this idea possible. I also remember looking up Dumbo in the 1941 Film Almanac at the research library, and seeing a running time longer than the present print of 64 minutes. I've put this issue into a footnote because I'm willing to believe that a.) The whole thing is just hooey, or b) Some basic book on Disney animation has a simple answer to my question. Savant has read a few books on Disney but certainly not all of them. Just the same, I've always thought the basic idea was sound. Dumbo is almost perfectly structured, and having the crows show up only for the "magic feather" scene—when they're already seemingly hip to the little elephant's state of disgrace— looks suspicious.

I can't recall ever hearing of such deleted footage before, and I doubt that it exists (or existed); but stranger things have been true. Perhaps there were story sketches up at one point for an earlier appearance of the crows; perhaps the live-action reference footage of two black dancers morphed into deleted animation footage over the years. Anyone?

July 11, 2007:

Woody'n You?

Today's the day for the Woody Woodpecker hoopla referenced in my July 6 item, and Randy Watts has entered this caveat, with which I must concur:

I do agree that it's good to see a studio give this kind of buildup to a classic cartoon release. I just wish the sendoff was for a group of cartoons I liked better than the Lantz shorts. Oh, I don't think they're terrible, by any means. Just seems like whatever talent and promise that went into even the best of them usually wound up being defeated by tight budgets and sloppiness. The Lantz shorts aren't like, say, Terrytoons, where one generally gets the feeling that nobody gave a damn so long as the films were completed on time. What makes the Lantz shorts so frustrating is that—at least into the 1950s—one gets the impression from them that there were people coming into the studio who cared and who were really trying to make better cartoons. Cartoons that were something more than the next deadline. Yet, the Lantz shorts always seems to fall short of the mark, at least for me.

A super send-off for, say, a complete set of Tex Avery's MGM cartoons would be better, but we'll take what we can get.

July 6, 2007:

Bits and Pieces

° It's encouraging to see a DVD set of classic cartoons getting a sendoff like the one for the new Woody Woodpecker set that will be released July 24. The major pre-release event is at 7:30 p.m. next Wednesday, July 11, at the Chinese Theatre complex in Hollywood. The people on stage will include Leonard Maltin, June Foray, and Phil Roman. To sign up to attend or to view the proceedings online, click on this link.

° It's encouraging to see a DVD set of classic cartoons getting a sendoff like the one for the new Woody Woodpecker set that will be released July 24. The major pre-release event is at 7:30 p.m. next Wednesday, July 11, at the Chinese Theatre complex in Hollywood. The people on stage will include Leonard Maltin, June Foray, and Phil Roman. To sign up to attend or to view the proceedings online, click on this link.

° To drop back about eighty years...in going through 1928 issues of Variety, I was struck by ads and reviews for the "Color Symphonies" produced by Tiffany-Stahl. Those sound shorts, in "natural color," bore such titles as The Toy Shop and In a Chinese Temple Garden. A review of In a Persian Garden that appeared just before Steamboat Willie's premiere in November 1928 described the "Color Symphony" as "Perhaps the first color picture with sound. ... Sound effects with song. Latter supposed to be sung by the girl principal but doubtful. She strings along with lip movements, however." Probably these shorts bore little resemblance to the Disney Silly Symphonies, but it would good to know if there's any possible connection. Do any of these shorts still exist? Has anyone seen any of them?

Surf's Up

I saw it a few days ago on the recommendation of friends, despite my growing skepticism about non-Pixar CGI features (this one was made by Sony's animation studio). For its first ten or fifteen minutes, it's easily the funniest CGI feature I've ever seen, but either the mock-documentary format couldn't be sustained or, more likely, someone up the executive ladder decided that the film needed "heart."

I saw it a few days ago on the recommendation of friends, despite my growing skepticism about non-Pixar CGI features (this one was made by Sony's animation studio). For its first ten or fifteen minutes, it's easily the funniest CGI feature I've ever seen, but either the mock-documentary format couldn't be sustained or, more likely, someone up the executive ladder decided that the film needed "heart."

As a result, the notion that we're watching a deadpan comic version of an ESPN show vanishes for long stretches while a more conventional talking-animal story takes over. The cast, made up mostly of penguins, summons thoughts of the dreadful Happy Feet, but it's the resemblance to Pixar's Cars that's most suspicious, and most unfortunate, especially during the climactic surfing contest.

I hear occasional laments that there has never been an animated feature as aggressively comic as the best Looney Tunes. Madagascar came pretty close, but Surf's Up really could have tested the viability of such a feature. Too bad no one in charge had the guts to risk making an unbashedly satirical comedy.

At least the movie looks awfully good. As Ratatouille also reminds us, the refinements possible in CGI—the rendering of surfaces, the illusion of camera movement, and so on—have become simply amazing, if not quite amazing enough yet to banish the nagging sense that we're watching puppets rather than living characters.

Walt and Stravinsky

Don Draganski, whose essay on Walt Disney's encounter with Paul Hindemith I posted here a few months ago, writes about a sidelight of Walt's much better known dealings with another famous classical composer, Igor Stravinsky:

In going through Vol. 3 of Stravinsky: Selected Correspondence (Knopf, 1985), I ran across a letter dated May 1, 1938, that Stravinsky wrote to Willy Strecker, who was head of the German publisher B. Schotts Söhne:

"Now something else: Walt Disney's proposition [presumably in regard to an animated version of The Rite of Spring or some other work; this was very early in the planning for what eventually became Fantasia] inspired me with the idea of composing something original for him, i.e., for animated cartoons. I am going to mention this to my agent in New York, Mr. Maurice Speiser, who is prominent in America in the field of film contracts, etc. Soon he will be moving to Hollywood , and he intends to give special attention to me. Thus his move there is very timely."

Strecker's reply is dated May 17:

"To make an original film with Disney is an excellent idea, but I do not know what he will think of that. You will have to discuss it with him. It is difficult for me to judge whether he is enough of an artist to create a truly original work in collaboration with you. Incidentally, I was amazed to learn that, to date, Disney has just broken even with his films because his production costs are so high; only Snow White was a real financial success."

The Germans were evidently quite well-informed about Hollywood, despite the Nazi administration. Of course, once the war broke out, Stravinsky was no longer able to maintain contact with his German publisher, and all royalties were either put into a special government-controlled escrow account or assigned to an American publisher who acted as proxy until the end of the war.

As evidenced by the letter Don Draganski quotes, Stravinsky began with real enthusiasm for Disney, but that enthusiasm lasted only so long as there was the possibility that he could make some money out of the association. Once that possibility had evaporated, his remarks about Disney were unremittingly harsh.

Just in case you've wondered, Stravinsky and Hindemith were friends, although Stravinsky described one of Hindemith's works as having "all the juice and flavor of cardboard." As the saying goes, the man's tongue could etch glass.

July 3, 2007:

What Harry Did

I wrote about Harry Reichenbach on May 24 and June 4. He was the famous publicist who was, in Walt Disney's recollection, managing the Colony Theatre on Broadway when he arranged Steamboat Willie's premiere there on November 18, 1928. That seemed like an odd job for a high-powered publicist, and when I finished writing The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney I'd not yet found independent confirmation of Reichenbach's role at the Colony.

Now I have. Here's the entirety of an item in Variety for November 14, 1928, just four days before Steamboat Willie's debut:

REICHENBACH'S YEAR

After working on a week to week basis, Harry Reichenbach has signed a year's contract at a flat salary with Carl Laemmle as special exploitation man for Universal pictures and theatres.

Reichenbach also has a percentage inducement if his publicity and exploitation can send the Colony, under U. lease, over a certain figure each week.

So, maybe not "manager" exactly, but close enough. Reichenbach was no doubt empowered to make deals like the one he made with Walt, probably just a few days before the premiere, whatever the exact content of that deal was. (Was Walt paid or not? No way to know for sure.) Reichenbach's savvy was confirmed by the press response to Steamboat Willie. Variety's reviewer, "Land," actually gave it two raves in the November 21, 1928, edition, once in a review of the Colony's stage show and another in a review of the cartoon itself.

The review of the stage show said that Willie was "synchronized with sound effects by RCA Photophone," and of course it wasn't. The cartoon's sound was recorded with Pat Power's Cinephone system, which was what Variety called "an indie [i.e., independent] device"—but it was projected on equipment licensed under patents held by Western Electric. Such "interchangeability" was a hot issue in the chaotic early days of sound, when Western Electric, an arm of the old AT&T, was trying to establish a virtual monopoly over the recording and projection of sound movies. The Colony, when it showed Willie, was, Variety reported, "the first wired Broadway house to run indie sound over its WE equipment."

The review of the stage show said that Willie was "synchronized with sound effects by RCA Photophone," and of course it wasn't. The cartoon's sound was recorded with Pat Power's Cinephone system, which was what Variety called "an indie [i.e., independent] device"—but it was projected on equipment licensed under patents held by Western Electric. Such "interchangeability" was a hot issue in the chaotic early days of sound, when Western Electric, an arm of the old AT&T, was trying to establish a virtual monopoly over the recording and projection of sound movies. The Colony, when it showed Willie, was, Variety reported, "the first wired Broadway house to run indie sound over its WE equipment."

Variety noted in that same November 21 issue that "no company has yet accepted ... the distributing privileges of this cartoon by Walter Disney and 23 others which he plans to have sounded with Cinephone." That was true, and it was almost certainly Walt's association with Powers's legally suspect system that made distributors reluctant to sign up. Eventually, it was Pat Powers himself who distributed the Disney cartoons.

July 1, 2007:

Ratatouille Revisited

I saw it again on Friday afternoon, and I've appended some second thoughts to my review.

I've read a lot of other reviews at this point, but the best I've seen is Jenny Lerew's, at her Blackwing Diaries blog. I particularly enjoyed her invocation of E. B. White's animal stories, like Charlotte's Web. I'm not a great admirer of those books, but I understood immediately what she was getting at.

There's a phrase in a biography of Beatrix Potter that may be still more relevant to Brad Bird's handling of his animal star. My memory of the exact wording is undoubtedly off, but the biographer, Margaret Lane, said something to the effect that Potter's animals, squirrels for instance, were faithful to squirrel character if not to squirrel habit. Remy, on the other hand, is frequently faithful to rat habit—he scurries most convincingly—but not at all to rat character. It's an acute awareness of that rat character, I think, that has made the film so difficult for some other people, like Michael Sporn, to accept.

Jenny questions my skepticism, in my original review, about the film's depiction of Paris light, and to a large extent she's absolutely on target. Some big-deal scenes in the film are simply too lush, but in many others—usually scenes in which the backgrounds are not a big deal—the handling seems just right. Like Michael Giacchino's score, such backgrounds support the film so skillfully that their excellence is all too easy to overlook.

Barks Up for Bid

I'm late in mentioning this, but the sale of items from Carl Barks's estate, which began with the Bonhams auction mentioned here last month, is continuing on eBay. Click here to go to Jerry Weist's eBay listings.