INTERVIEWS

Maurice Noble: Four Interviews

By Michael Barrier and Milton Gray

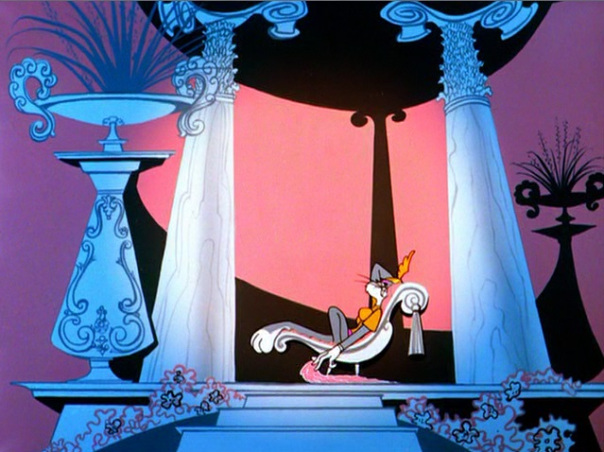

| From What's Opera, Doc? (1957), the most famous and admired of the cartoons Noble designed for Chuck Jones. |

From MB: Maurice James Noble (1911-2001) is probably the best known and most admired of the designers for the Hollywood cartoons of the 1950s and 1960s, in his case the Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. I hoped to interview Noble in 1976 during a marathon research trip to California for my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age , but that turned out to be impossible. So Milt Gray filled in, recording an interview with Noble at his home in the Los Angeles suburb of La Crescenta in January 1977. I subsequently interviewed Noble myself on three separate occasions in 1989 and 1990; I believe Milt was with me on all three occasions, although the transcripts don't always reflect that.

It's unusual for me to post a group of transcripts from interviews with the same person, but this time it seemed like a good idea, because the content of the interviews overlapped so heavily. I think that reading the interviews as a group also minimizes the weight of inconsistencies—and there are some, especially as regards chronology. Here is a highly compressed but, I think, accurate version of his work history: Maurice entered the anmation industry in the mid-1930s as a background painter for Disney, lost his job at the time of the 1941 strike, entered the army in the Frank Capra unit, after leaving the army worked briefly for Warner Bros. in 1946 as a background painter in Chuck Jones's unit, worked for several years on Lutheran filmstrips in Saint Louis, returned to Warners in 1951 as Jones's layout artist, left the Jones unit shortly before the cartoon studio closed for six months in mid-1953 to take a job with the industrial film producer John Sutherland, returned to Warners in 1955, stayed there until the cartoon studio closed in 1963, then worked for Chuck Jones at his new MGM studio. I'll revise and expand this paragraph as greater precision becomes possible.

I sent copies of the transcripts of all four interviews to Maurice for his review, and he made mostly minimal changes, asking that some material be deleted because it seemed too personal.

January 24, 1977

NOBLE: While I was at Disney's, years ago, my first screen credit was on Snow White, and I did creative sketch work on Bambi with Tyrus Wong, and creative sketch work on Fantasia. I did the color coordination and a lot of the design and had screen credit on Dumbo. I did some backgrounds and sketch work on Pinocchio and The Old Mill over there, besides a lot of short subjects.

After I left Disney's [a move that Maurice said in a note was "related to strike"], I was in the army, and I was with Frank Capra. We worked on the Army-Navy Screen Magazine over there; it included the Snafu cartoon series. Chuck Jones directed a lot of those. And we did a lot of graphic inserts for the Screen Magazine. That's when I met Ted Geisel—Dr. Seuss. He was my commanding officer over there. He didn't know anything about animation at the time.

After I left the army, I worked at John Sutherland Productions, and I designed the special animated film that they made for the inauguration of the stainless-steel retractable dome for the big concert hall in Pittsburgh. Dimitri Tiomkin did the music for it, I laid the picture out and designed it, and Eyvind Earle painted the backgrounds I designed. [William] Steinberg [conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony] was supposed to conduct the music, but when he looked at the score, an animation score—how they break and cue and so forth—he said he would have nothing to do with such junk, so Tiomkin not only scored the picture but directed the orchestra.

Then we did a couple of films for the Sloan Kettering cancer foundation; my job, on all of these productions, was designing and layout. Irv Spence was working there at the time, and Carl Urbano; I think Carl Urbano did some of the directing [of the Pittsburgh film]. I think Bill Melendez was over there, too, at the time; I vaguely recall seeing him around there. My jobs always kept me off in a little corner by myself, doing sketch work and continuity stuff and just working with the director or producer. I didn't get involved too much with the production end.

John Sutherland was a very interesting man. He wanted to be another Disney, in a way. It was all quality; he had the gilt-edged clientele, like U.S. Steel and Sloan Kettering—all big accounts like that.

GRAY: He started around 1944, didn't he?

NOBLE: Somewhere along in there. I think that when I was in the service, he was producing something, and I did some work for him. This was when they would sub-contract from the Capra unit, and material would go from Capra to Warner Bros., or Sutherland, or Disney's. If I had designed something, or laid it out, I'd have to go over there and be sure that it got off on the right track. After I got out of the service, I worked for Sutherland for a while, and then Warner Bros., and back to Sutherland, and back to Warner Bros.

GRAY: Did you work exclusively for Chuck Jones at Warners?

NOBLE: I did one picture with [Robert] McKimson; I forget whether his layout man was absent, or what happened. I didn't work for Friz Freleng. After Chuck left, we were involved in The Incredible Mr. Limpet. I also worked on the Bell Telephone science series; maybe I worked with Friz a little bit on one of those, and I worked with Chuck on one of those. Chuck did one called The Human Senses, I think it was, then he left. I think that was the only one Chuck did there.

Later on, after they closed Warner Bros. [the cartoon division], there was kind of a hiatus for a lot of us. Chuck started the MGM studio, and I became the design nd layout director. We did some Tom and Jerrys and branched out from that. I designed and co-directed The Dot and the Line. Then MGM closed down, and I went with Ted Geisel out to DePatie-Freleng, and did The Cat in the Hat and The Lorax. I think that the last one I worked on over there was the trilogy,Dr. Seuss on the Loose, about three years ago. Then I decided to retire.

GRAY: At Disney's, did you work directly for Joe Grant, in the character model department?

NOBLE: No, I didn't.

GRAY: I heard that while you were at Disney's, you worked on The Brave LittleTailor, and you did several model sketches in colored pencil.

NOBLE: I have no recollection of that. I remember Water Babies, and Wynken, Blynken and Nod. I think I set the original color models of Huey, Dewey, and Louie, Donald Duck's nephews.

GRAY: I'm not sure that I have a very clear picture of exactly what you did at Disney's. Were you designing—?

NOBLE: When I first went there, I painted backgrounds. From backgrounds, I got into color coordination.

GRAY: That's selecting the colors for backgrounds?

NOBLE: Sometimes it was backgrounds, and sometimes it was selecting colors for [the animated characters], talking with the directors and the background men on the proper colors for the animation, so it all fit together. I kind of drifted from that into inspirational sketch stuff. I did literally thousands of sketches for Bambi. The famous Swedish illustrator Gustaf Tenggren, started designing Bambi. Tyrus Wong and I did most of the sketch work for Bambi. They were little thumbnails [he indicated they were about 4 x 5], in full color—watercolor, or opaque, whatever happened to be convenient.

GRAY: What were you aiming for in those sketches? What were you trying to explore, or to accomplish?

NOBLE: Perce Pearce, I believe, was directing, and he'd give us a hunk of script, and he'd say, "We need to have something on the forest in winter." I'd do a whole series of forest-in-winter sketches. Or he'd come in and say, "What do you see this forest as being like?" We were exploring forshots, and ideas, and atmosphere, and composition. Ty and I were really building bonfires under somebody else's imagination to see where a director would take it. We were free to roam anyplace with our ideas; it was a great year and a half.

GRAY: Were they trying to bring in animators at that point, or was this prior to any serious thought of bringing in animators?

NOBLE: There was some exploratory animation done. Some of those reels were amazing in their intricacy, in the final production. I remember I did a whole series on the start of the forest fire, and I tried to sell them on the idea that they should start this thing out almost with an abstraction—bright red flicks against dark blue, and how these things dance through sky and finally ignite, hit something and flare up almost like fireworks, and hit the next tree, and so on, until it was an inferno. At that time, they weren't buying anything that was far out—to them. They took my more realistic sketches and [used them]. We had a total unit, set up separate from the [main] Disney studio. We worked independently; I don't recall Walt ever coming down there. He might have been up front. Probably once a week Perce Pearce and Tom Codrick would come into my cubicle and I'd have a whole wall of sketches, and Tom and Perce would say, "I kind of like that one," and [so on]. A secretary would take a numbering machine and stamp numbers on all of these sketches. She pulled down everything except the ones they'd said they liked, and I'd never see them again. Perhaps they went to production—but "fresh approaches" was the idea. They'd be all filed away, and I'd be left with four sketches out of a whole wall of sketches.

GRAY: I'm surprised that Walt wouldn't come by and take a look at those, because maybe he would have liked certain things that they didn't.

NOBLE: He wasn't one to let things go that long, to keep his finger out of the pie that length of time..I imagine they did go back to the main lot, and Walt probably looked at them. He was generous with time, but I'm sure I wouldn't have sketched that long on it if I hadn't been ringing some bells someplace.

GRAY: Were you trying for a new look in the film, something different from the traditional ink-and-paint animation?

NOBLE: I think so. I've always been interested in exploring ideas.

GRAY: I mean the studio, as well as yourself. Were they consciously trying to develop something new?

NOBLE: I know I was. The Disney studio locked in and locked out ideas. Let's put it that way. I frankly was disappointed that they lost the essence of the book, which was the grandeur of the forest. [[Instead], one got Thumper, and looking under all the petunias. I would say that the sketches I was working on had more of the solemn quality that one gets in the big redwoods, or something like that. The grandeur of a tremendous forest, instead of down among the blades of grass. To me, the picture was a bit of a disappointment, visually, after having poured so much time into it.

GRAY: The two times you worked for Warner Bros., were both for Chuck Jones?

NOBLE: Yes.

GRAY: Do you remember the dates when you started there, left, and came back again?

NOBLE: I really have vague recollections of that period. I was with Chuck for a while when we were over on Van Ness Street, the old Warner Bros. cartoon building there...

GRAY: When you left Warners, and then came back, was that that period in '53, when they shut down for six months?

NOBLE: They shut down for six months, and I was over at Sutherland's for part of that time.I worked for Chuck for a while, then I went back to St. Louis and worked back there for a while, then Johnny Burton sent me a telegram that said, "We have a job waiting here for you, do you want it?" By then I'd had enough of St. Louis, so I said to send me a written confirmation of this. He did, so I was able to present that to my boss. I was doing filmstrips for a Lutheran minister who was producing vidual aids, and I had gone back there with the idea that I would become part of the company: it seemed like a good idea at the time. It didn't develop: there are fast talkers even in the church business. I built up the department from myself up to six guys, working on this material, and nothing was forthcoming, so I took Johnny Burton's offer and came back to California. That's when I started to work for Chuck again.

GRAY: Was that before or after Warners reopened in '53?

NOBLE: That was before. Later it shut down, and I went over and worked at Sutherland's. Everybody thought I had inside information on it. I had asked for a raise and Mr. Selzer had turned me down, and I said, "Mr. Selzer, that being the case, I guess I'll just take John Sutherland's offer." This was just before they were going to close the studio. The morning I was going to go over, Mr. Selzer called me in—he always called me "Murice"—and he said, "Murice, how much they going to pay you over there?" I told him, and he said, "We'll match it." I said, "It's too late, I've committed myself over there." He was a funny little guy; he stood up and leaned over the desk and said, "Let me shake your hand." He shook my hand and said, "Anytime you want a job, come back and see me." So I always had a job when I went to see Mr. Selzer. It was only a week or two later that they closed the studio. I didn't know anything about it, but everybody assumed that I did.

GRAY: The closing must have been awfully abrupt, then.

NOBLE: Oh, yes, it was.

[Taping resumed after an interruption.]

NOBLE: The last backgrounds I painted were at Disney's. When I worked with Chuck, he'd give me a general rough idea of what the picture was about—sometimes he'd have a synopsis of it—and I'd take it back to my room and do a lot of creative thumbnails on the thing. what I thought would be an appropriate approach. The design comes from within a story; you don't graft the design on top of it. Generally, I was trying to make it acceptable to the average viewer—a chair was always a chair, and a door was always a door, and so on—so that he didn't have to struggle to get the idea. I'd try to make it agreeable in design and color and so forth. If it was a dull picture, I'd try to make it interesting for myself, by making something interesting out of it. Lots of times, I'd do sketches, and I'd be working on it, and I'd get an idea, and I'd jot it down. Then I'd take it in and talk to Chuck, and when we arrived at how we thought the picture should go, I'd go off in my corner and I'd design the thing. He'd rough out his own animated scenes.Sometimes I'd get the outline of the story way ahead, even before he started to lay it out.

GRAY: This is something that you mentioned in the interview you did with Joe Adamson that I was curious about. You said that you would talk to Chuck, and sometimes you would get a rough storyboard, sometimes just a story outline. I wondered if Chuck was thinking up these stories, or Mike Maltese...

NOBLE: I didn't contact Mike a great deal. We were great friends, and we used to explore antique shops on the noon hour; he's a great guy. But I always worked with Chuck. In earlier years, working with him, he'd give me a resume of the story. Sometimes, he'd have his whole pictue laid out—wrapped up in the pink exposure sheet—and I'd flip through the thing, trying to get an idea what it was all about. He'd have given me a five-minute run-through of the cartoon, sometimes on the boards and sometimes verbally. I would have to hitch this thing together by flipping his rough layouts.

GRAY: Did Chuck ever write his own stories, or did he rely on Mike for that?

NOBLE: In the early years, Mike would get a nucleus of an idea—or Chuck would—and Mike would go through and thumb nail the thing, and story-sketch.

GRAY: I would have assumed, that by the time it was ready to shown to you, Mike would have had the story worked up, at least in thumbnail form.

NOBLE: He would, in his own inimitable way of doing things. The story was put over, but Bugs Bunny didn't look the way Chuck would draw Bugs Bunny, but you knew it was Bugs Bunny. I could get an idea of what the story was.

GRAY: If those boards were done, why would Chuck sometimes only have a resume, or a script, or something like that, instead of a board, to show you?

NOBLE: When it left Mike's hands, Chuck would start laying out, and he would get a section of the picture that he fell in love with, and this would expand, and all of a sudden he was cutting this, and cutting that, to make room for it, and still bring it around full circle, so it would still have some solution at the end. Many times, he dwelled lovingly on something at the beginning of a picture, and everything had to go crazy at the end, to resolve the thing. By that time, Mike was on another story, and Chuck was working on it, and I would go in and run through a picture with Chuck. Sometimes he'd say, "We're going to cut this," or "This is the way it's going to work now," and so forth. I was across the hall, and once in a while I heard some loud voices; I assume that Chuck and Mike weren't having a meeting of minds about some story point.

Chuck was always his own boss, when it came to the ideas. Of course, I didn't always agree with Chuck. But I realized, and I'm sure Mike realized, that when you work with any director, he is kingpin. His name is on the thing, and his stamp is on the thing. You can argue until you're blue in the face, and lots of times you can convince him. I was great at arguing; he complimented me one time and told me he bought at least 90 per cent of my ideas. But I was always careful to be pretty sure of what I was going to take into him. It wasn't a picayunish thing. If there's a pan, and there's a big jolt in the middle, and it doesn't feel right, you try to see what's wrong with it, whether it's visual, or story, or what, and you try to work out some solution, and you take it in to him, and say, "Look, maybe it would work better this way." This was the working relationship we had. If it was a kind of run-of-themill picture, and I had an approach on it, I'd take a few sketches into Chuck, and he'd look at them and say, "What are you bothering me for?" And I'd go back and do it. Lots of times, it would get up on the screen, and he'd do a double-take, because it wasn't exactly what he had in mind, but it worked. I had visually solved it in a different way than he had solved it, in animation. It would work with the animation, but I had re designed the set-up. This happened occasionally. After so many years, we had a kind of rapport. Three or four key sketches, and he'd know what my intentions were.

GRAY: What form did these sketches usually take?

NOBLE: They were usually 4 x 5; always in color. I did all of my sketching in color, and then I would work with the background.man. I worked with Phil De Guard for a long time, one of the greatest, and then, when we expanded, we had numerous background men there. This was when we did The Phantom Tollbooth.. When Phil De Guard was my background man, I'd go up and talk with him. The idea was to make a strong suggestion, but you want to feel that that background man is contributing also. I always insisted that I not only control the layout but that I control the color, because when you're designing something, a linear pencil design doesn't mean anything unless you're visualizing this in terms of volume and color and so on.

GRAY: So the background artist was more or less your assistant, unlike it is today, when the background man takes over.

NOBLE: Yes, it was more or less in that vein. Phil De Guard and I had great rapport; we worked together for 12 or 15 years. He was stubborn once in a while: I'd ask for something, and he wouldn't want to do it that way, and I'd say, "Come on, just for kicks—you've done it your way, now let me see it the way I have interpreted it." He'd kind of grumble, but he'd go ahead and do it. If his way looked better, I'd buy his, and if my way seemed to be the best way to do it, he'd go ahead and do it my way. Sometimes it was the tonality of a running color that we were going to use for a color theme. You're designing for length; a still painting or design sits there, and your eye wanders around it, and you find basic colors and accents and darks and lights and so forth, but when you design in animation, this is in "blips," so to speak. You're going to see a long period of blue, then a blue with accents of red and yellow on it—staccato forms, or something—then back to a long stretch of blue, and maybe a transition into a warm color. You're seeing the composition in length, on this motion-picture screen. The design is passing before your eyes in a pattern of color that you're only seeing a portion at a time, but you're reacting to it in terms of time [i.e., in terms of what has already been shown, as well as what is being shown at a particular moment].

The whole thing is the animation. You can enhance it, and build around it, but the center of interest is the animation.I'm sure you've seen plenty of animated backgrounds that, when they stop, the pole sticks straight out of the top of the head, or something. This is because they really haven't planned; they look at a layout, or a background, and say, "This is complete in itself." But it isn't; all it is, is a framework for that spot of animation. Consequently, whether you've moving, or in a [held pose], I would always sketch in maybe three or four drawings of the extreme of the action, on the layout that I was working with, so I would know exactly what I was doing. Then I could elaborate around the outside, or support the action, or whatever it happened to be. Graphic fun and excitement that loses the action is poor design.

GRAY: Would you do this planning before or after the animators had finished the scene?

NOBLE: I would work from Chuck's roughs. He would do the character layouts, I would take the exposure sheet, I knew how much footage we had, I knew the continuity. Usually, I would figure all the speeds of all the pans, so that by the time the animator got it, he got a rough layout with all the stops and starts and everything.

GRAY: That's unusual. Today the animators have to figure that out themselves, to a large degree.

NOBLE: I would try to give a working layout to every animator.That would stay right with the scene. Movement is also part of the design.

GRAY: You had to assume, then, that the animators would stick pretty close to the character layouts.

NOBLE: They had better!

GRAY: Would Chuck approve, or permit, the animators to occasionally put the characters in different parts of the screen than envisioned in the character layouts?

NOBLE: I'm sure he was open to ideas within limits. Ordinarily, the animators stuck very closely to Chuck's layouts.

GRAY: Because they were that well thought out.

NOBLE: Yes, and the expressions, the extremes—these were all indicated with the three or four drawings that he would insert with the scene. Chuck was "acting." When the animator got a scene, ordinarily he would have Chuck's layouts and a rough layout of the background, which I would do. Sometimes, it got out of hand—because of production [problems], or something like that—and I would have to call a scene back from the animator; if I knew he was going to work on a still, for instance. We had what we called a poop sheet, and it gave stills and pans and so forth, and footages. The picture was totally organized, as it came from Chuck. He would make a copy for himself, with all the footages, and maybe even a little of the dialogue or description of what happens. This was on a big sheet [about three feet square], ruled off. He could look down this poop sheet and see the total picture. He would call me in and give me a rough outline and flip through the scenes with me, lots of times, before he'd handed it to the animators. I tried to be close to Chuck; we were exchanging ideas, and he was sketching characters and I was doing backgrounds and design ideas. Sometimes the stuff would go into Chuck, and a design idea would be clipped right in with the scene. He'd say, "I like your approach here, let's kind of develop this and use this in this area here. It had gone to him earlier, and then it would come back to me and I'd continue developing the idea as I saw the way he had developed the action

The animation was Chuck's baby, although some of the animators were amazingly good; Ken Harris was very good at adding something to a scene, within the framework that Chuck had laid out. He always had some little bit of action, something almost grotesque, that was always very funny.I always said he looked like Wil.e E. Coyote, and he helped develop that, I'm sure.

I was a big militant against violence in cartoons; I used to go in and talk turkey to Mike. Of course, when I first started working in cartoons, violence was the big standby for laugh material. I would have big arguments with Mike when I'd see what he was doing on the storyboard. He used to cringe, finally; he'd see me come in and say, "Don't look at this portion!" I'd say, "You've got an axe again, don't you?" or "Where's the dynamite going this time?"

GRAY: On your background layouts, what would Chuck usually give you? How complete would his descriptions of what he wanted for a background layout be?

NOBLE: He ordinarily left it up to me to come up with something.

GRAY: I'm assuming that he would give you a very loose sketch that would be very little more than a horizon line and maybe a line to suggest a corner of a building, or something.

NOBLE: That's right.

GRAY: On the layouts that you did, on what percentage, roughly, did you indicate what kind of colors that you wanted?

NOBLE: I'd key it, all the way through. If, say, a series of actions happened in a given room, and then they moved into another room, there'd be a color scheme for one room and then a color scheme for the next room. If I had an extreme pattern or lighting effect that I wanted, I would make a rough on that.

GRAY: Were these color roughs on the same piece of paper as your actual layouts, or on overlays, or—?

NOBLE: They were on separate pieces of paper. Sometimes they would be the size of the sketches; more ordinarily, they would be little small things.

GRAY: So it wouldn't necessarily match, right to your layout drawing.

NOBLE: No, no. When I was sketching an idea and trying to get a color scheme, I might, during the period of time I was trying to get the idea together, have five or six or seven color schemes,before I finally decided which way to go. All the rest of them were dumped. Then I would coordinate, and make enough color sketches and notes, so that when the background man picked that up, he knew where he was going, all the way through.

GRAY: What medium would you use for those color sketches?

NOBLE: I used the regular cel paint. I would get little jars from the ink and paint department, and I would paint in those colors. This is what the backgrounds are ordinarily painted with. They adhere: they have binders in them, and they hold up well under the camera. And a lot of the colors are very fine, well-ground colors. You let them down, and you can use them almost like watercolor, or else you can go clear to opaque, and use them like opaques. They were all water-based paints. Some designers, at Disney's and so forth, would use designer's colors. These are very brilliant colors, and there were things that were not compatible with the cel colors. So I thought, why not design in the colors that were going to be used in production, and be compatible with the animation? Consequently, I always used the cartoon colors.

GRAY: When you did your sketches, did you do them on animation paper, or illustration board, or background paper—?

NOBLE: Usually on something like a Strathmore of some kind. I painted on whatever happened to be there, but usually background paper. A rather heavy bond paper. I'd have them all cut up in little hunks, and I'd tape them on a little board, and sit there and paint them up. Then I'd have somebody cut a bunch of mats, and we'd just paste them in there so we could look at them—usually a black mat.

GRAY: There was a period at Warner Bros.—and I think this was when you were there—when the background artist would cut out pieces of eraser and dip them in ink and stamp them on the paper; this would be like for the leaves on trees.

NOBLE: I originated that idea. Little stamps, and things like that.

GRAY: A couple of friends of mine commented one time that they were disappointed just in the cartoons you did with Chuck in which you used this rubber-stamp look, because, to them, it had more of a self-conscious graphic look. I was wondering how you might respond to such criticism.

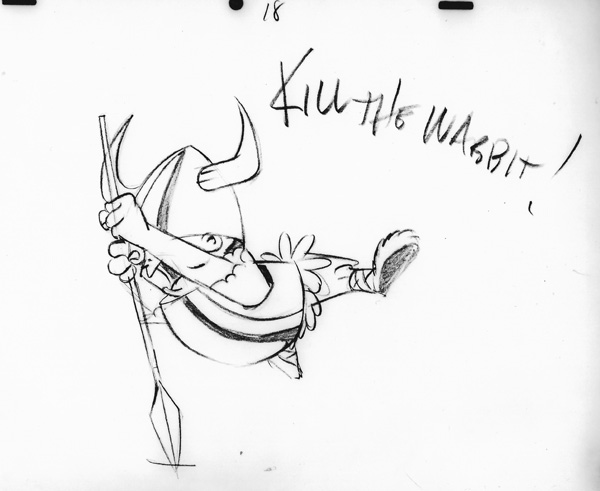

NOBLE: It was strictly a graphic gimmick. We had to have a Sherwood Forest—I remember that was Robin Hood Daffy, that one I remember particularly.

| From Robin Hood Daffy (1958), one of the cartoons for which Noble introduced "graphic gimmicks" like rubber-stamp leaves. |

GRAY: I don't recall exactly how that one looked. The ones I'm thinking of had to do with the wolf and the sheep-dog [Sheep Ahoy and Steal Wool].

NOBLE: These gimmicks were time savers.due to the great number of backgrounds in Chuck's pictures. You're thinking about the little stippled bushes, and things like that. That kind of evolved between the background man and me. He'd lay in a big wash of color and then make these little bushes. It gave a certain style, and suggested desert growth and was quick and easy. After all, we did 13 cartoons a year, and that meant, really, going at it.

GRAY: So it was done primarily for economy reasons?

NOBLE: Yes. Sometimes it was economy, sometimes it was styling. You got tired of painting the same old sagebrush that way, so you evolved another style. After all, we made I don't know how many of those things. And Chuck's staging and timing were such that you couldn't re-use them. Poor Phil had to paint those things, and sometimes we'd have 92 backgrounds in one short subject. I tried to design it in big areas that I thought would design well as it moved through, and then give him a few sky shots—card backgrounds, or low horizons with nothing in it except a blue card. To make it easier for him.

GRAY: And some of those backgrounds would be enormous pan backgrounds...

NOBLE: Phil De Guard had a great big long shelf, and the rolled-up pans and a stack of stills would be just jammed upon it, for one six-minute short subject Because the staging changed all the time. Also, I didn't like to see the same telephone pole come through 26 times; I thought this was a horror, so I kept designing new pans, or shapes, and eventually out of this sandstone, on the Road-Runners, for instance, we got more elaborate and fantastic; I remember the stipple bushes, now that you mention it. In a sense, the RoadRunner and Coyote were a stylized type of story and action, and so the backgrounds became more stylized.

When I had a particular picture to do—say a Pepé le Pew, which was French—I'd get a whole bunch of scrap, and I'd look at table legs and chair legs and doorways and Cupids, and all this and that. I'd study the darned stuff, and thumb through pages and pages, for, say, two days. Then I'd bundle it all up and put it away. As I drew and designed, I'd mentally say, "That leg went this way; okay, let's exaggerate it." When you design for cartoons, you have to exaggerate the form, because you only see it a short time. You must grasp everything in a split second, lots of times. If you didn't, you wouldn't have any essence, of visual impact.

GRAY: Would you exaggerate something more in a short scene than in a long scene?

NOBLE: Right. Also, an exaggerated form has a certain amount of humor in it. A French leg that is very properly French isn't nearly as funny as one that has a certain voluptuousness to it.

GRAY: How could you remember all that detail, even after studying it for two days?

NOBLE: This is because you're making mental notes. I could probably draw something now that would look, in an exaggerated way, like Madame Pompadour's boudoir. Also, practically any environment, if you're attuned to it, has. a certain quality about it, a certain essence.

[After a brief interruption.] Many times, I'd be ahead of Chuck, with sketch ideas. He'd give me a brief outline of what he was going after, and I would design material and hand it back to him, and he'd weave it back into the story, because it hit him right.

GRAY: Can you give me any specific examples?

NOBLE: I think What's Opera, Doc? was one of them. Some of the thumbnail stuff had been done by an artist no longer living—Ernie Nordli—and it was too straight. He was a great layout man in the Disney tradition, but not daring, and he was an elaborate nuts-and-bolts man. Then I came onto the production and Ernie left and went back to Disney's. I guess this was when I came back from St. Louis and started working for Chuck again. I threw all of Ernie's stuff out and started in again.

GRAY: How much had he done?

NOBLE: It was kind of in the formative stage—vague scatterings.

GRAY: Exploratory stage?

NOBLE: Sort of. There was a kind of continuity that had been worked on. But I immediately started to do all of these sketches on it, and it was kind of held up while I did sketches and ideas. I did a lot of sketches on the thing, and then I talked with Chuck about it, and we started to work on staging. I know that toward the opening, he wanted to have this big shadow going. So I did a sketch, and I put the tiny little character down in front of it, to give this gigantic scale. He bought the idea. As we worked along, the thing developed. Then I went to the pink roses and the Greek love castle on this very bazoomy hill; it seemed to be appropriate, and it gave us a break in staging. I was thinking now in terms of dramatic layout and staging for each section of the picture as it went along. It became theatrical; it wasn't reality. Super grand opera, as it were. We worked back and forth. I remember when Elmer was calling up the storm, I got the idea of painting the character in these bright reds, and just using a pen line. I selected the colors and sent them in to the ink and paint department, and Harry Love—I think he was in charge of the ink and paint department at that time—came back and said, "You mean to say you want all

of this painted red?" I said, "Yes, that's the way I want it." Friz came down and kind of looked around the room and said, "What kind of shit is this?" He was great at timing, but his imagination stretched from A to B.

GRAY: I've always been very disappointed by Friz's cartoons, and a lot of people in the business, from Warners, seem to disagree with me, and I've been trying to get a grasp on why I feel the way I do. To me, one thing that hurts Friz's cartoons is the design of the characters; they seem so bland.

NOBLE: They were obvious. Yosemite Sam is very obvious; and Tweety. The thing that makes Friz's pictures is his timing. They never explored an idea, or a situation, particularly.

GRAY: They're just kind of straight gag material.

NOBLE: Yes, it is. When I worked over at DePatie-Freleng with him, on the Dr. Seuss things, we'd get into corners, and you'd have to talk until you were blue in the face to sell an idea to Friz. [After some further discussion of the differing styles of the Warner directors.] Chuck's cartoons always felt good; and that was because he drew and laid out every single extreme for his whole cartoon. He'd sit in his room, and he was directing and timing and drawing all at one time, and this would go right onto this poop sheet, which was then transposed over to his exposure sheets.

GRAY: Would that be translatable? I thought the poop sheet was just a list of scenes.

NOBLE: Well, it had footages on it. He'd have a rough pink sheet, but it didn't have any timing on it, and he'd put these drawings in there—scenes 1 through 26 or 50 or 97 or whatever it happened to be—and through experience, he knew approximately how long he was going to have, whether it was going to be a two-foot scene or a five-foot scene, or a big super-long twelve-foot scene.

GRAY: So when Chuck did his character layouts, he wasn't doing any final timing, on an ex-sheet or anywhere else, he would just kind of rough-time it on this poop sheet.

NOBLE: Sometimes it kind of worked along that way. He knew where all his footages were going to go. But he'd fall in love with some gimmick or situation, so he'd drop something out here that was originally going to be in, and he'd add the footage up here, and expand the number of drawings in that, and then eventually, here was the total, over-all, of all the sheets. He'd run it into the adding machine, and it came out right. Or, if it was over, he'd tighten up a scene, or something. Lots of times, I would get the total picture and his rough layouts, and I'd go through the whole thing and get ideas of what the thing would be doing, if I hadn't worked ahead ·more with him on it, and get an idea of how the thing was going, and where my footages were. Then I would start designing. It would be about then that they would yell that they needed work for animators, so I would farm the stills out to the animators. The animators would be given sections; I'd give Abe [Levitow] or Benny [Washam] or Ken Harris the number of scenes I could let them have right then, then I'd have to plot the pans, and so forth, and give them a rough distance they were going to travel, and if they had to register to something, try to give them a registry, either in a stop or in a start position. It became kind of ticklish if they had three or four registrations on a given pan, and I'm working blind. So I would quickly make a shape, and then I had to make that thing work.That meant I had to have a pretty good idea of where I was going to go with something.

GRAY: Did that happen very often, that the animators were right on your tail?

NOBLE: Oh, lots of times. I'd get to working through and I'd go into the animator's room, and I'd say, "Let me borrow scenes 26 and 47, I need to get some extreme drawings I can put on the light board." I'd make some quick tracings, so I'd know where the extremes were, then I'd take them back and cook up a scene, to work around them. In the present system, the layout man is in effect a character layout man, he's not a designer, and I think this is where the fault comes, many times, in the

cartoons. There are some very capable background men, and

technically, they know all the tricks, but what they come up with doesn't have anything to do with what the cartoon is all about. And no design is worth anything if it isn't supporting the idea of what the story is all about. Lots of times I'd throw out stuff that I knew would be great on the screen but really wasn't good for the story. Sometimes my heart would break

when it was going to be in the story originally but there wasn't any footage for it, and out it would go. Particularly in all the years I worked with Chuck, he was great on all this close-up stuff. This is really what his cartoons are all about.

GRAY: That must have made it difficult to make interesting backgrounds sometimes, with the character dominating the screen in close-up.

NOBLE: Once in a while, I'd go in and say, "Can't we have just a little more footage?" He'd say, "Well, if you can get it off this and that... See what you can do with it." I'd check back with him, and then, when they got it all together, it'd be back the way he wanted it.

GRAY: How do you approach the problem when a character is in an extreme close-up, maybe in a dialogue scene?

NOBLE: I try to design enough interesting material in the footages that I am permitted—a pan, or an establishing scene—try to get enough stuff in there, for the amount of footage that would be allowed me, so that when I cut in there, the.audience would be oriented to this close-up over here, you're going to move right in on it. They've seen it in a long shot, so they can stay on close-ups quite a long time. Sometimes, as the character would move, I'd quite deliberately try to arrange the background to get a little something in the background, to get a feeling for the total, over-all, for a while; and then bring it back up to a close-up, where he's stopped again. An archway in a vista, or something like that—the essence of the scene, again. before moving in on this close-up. But you're always fighting for footage, for establishing shots. After I'd worked with Chuck a number of years, he would allow me six or ten or twelve feet or something, to try to get a shot in, so he could move in on his close-ups again. What's Opera, Doc depended very much on the super elaboration of all these scenes. I remember that goofy sway-backed love seat in the Grecian scenes, when Bugs was Brunnhilde. I designed that thing, and Chuck did these drawings, and I elaborated; I gave him the design, and he used different angles on it, and I had that curve to work with. Essentially, all he had drawn was a line like this [curved like the back of the seat], which came from the design I had given him.

The Ralph Phillips cartoons were some of my favorite cartoons. I did sketches along the line, as I knew the general essence of the story, and Chuck and I worked back and forth and wove this stuff together. Those things were pretty well pre-sketched; my design ideas were pretty well formed, and shown to Chuck, as he progressed with his layouts, his character layouts.

GRAY: So you had a better chance of control...

NOBLE: Of the design of the thing.

GRAY: Mike [Barrier] and I were wondering to what extent the original storyboard sketches would have suggested anything to you. I suppose they had all been done by Mike Maltese.

NOBLE: In the early years, yes.

GRAY: Did Chuck start to do them himself, afterwards? When you say "the early years," do you mean...

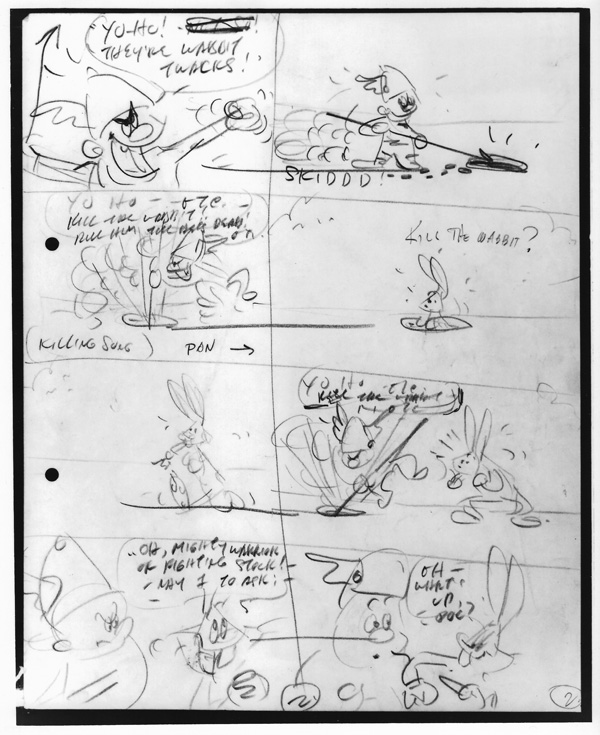

| Thumbnail story sketches by Michael Maltese for What's Opera, Doc? Maltese, Chuck Jones described the sketches, which fill several pages, as a "corrected storyboard," whereas Maltese said, perhaps more plausibly, that they were preliminary sketches. Noble said that they were "very typical of Mike's sketches." Sketches courtesy of Chuck Jones. |

NOBLE: Mike's were strictly thumbnails; when Mike was there, his story continuities were all in thumbnails. Chuck took these piles of thumbnails, and numbered them, and then he did his character layouts. Mike would always put over the idea—what the gag was—and the dialogue was right there.

I worked with Chuck's animation layouts, and with Chuck.

GRAY: Not so much from the storyboards.

NOBLE: No. Many times, I think, from Mike to Chuck there was a twisting of the material, so to speak.

[The conversation turned briefly to Walt Kelly.] Walt was a delightful person; I really enjoyed him very much. He had the room next to me [at the Jones studio]. He was a very charming man; in fact, he was Pogo. That kind of soft character, and real sweet. And work—oh, the way that man worked. Long hours, and fast, too. He did all of his story, and his drawing, and his inking, and lots of times his own lettering—he just wrote the stuff. He'd chuckle when he got some idea that tickled him.

GRAY: He enjoyed his work.

NOBLE: Oh, yes. I think he really loved Pogo; he loved his characters. Ted Geisel [Dr. Seuss] is a little bit the same way. He has a lot of vanity, but when you really get to know him, he's a very gentle, modest character. He's very simple, underneath all this notoriety.

GRAY: On Chuck, is there anything more you could tell me in regard to how involved Chuck was with the story material. I'm trying to get really clear in my mind on this point, because I had always assumed that as long as Mike Maltese was there, that Mike Maltese really did all of the writing, and then Chuck would take it and stage it and time it and act it out, but not be that involved in the writing.

NOBLE: I didn't become involved in Chuck's relationship with Mike. Chuck had a room here; Mike was on one side, I was on the other side, and the material was fed in from the two sides. I didn't know what was Chuck's and what was Mike's, when I got it. Chuck was always writing and rewriting stuff. But it was none of my business, actually, what went on in the story department. A little bit later, Chuck started to write an awful lot of his own story material. Trying to remember whom he had in there for story material after Mike left, I can't think of anybody. I think that the strong point about Chuck was that he was always exploring material. It wasn't as though he just had a given stable, a sure thing. and he wouldn't try an idea out here and there. I know that lots of times he had to plead, that he'd do three Road-Runners if they'd let him do this. That's the way some of these things were made.

GRAY: He would have to bargain with management.

NOBLE: Yes. [Reading from a list of written questions] "Did you work alone or did you have assistants at any time when you were working with Chuck?" The only time I had any assistants there, in designing, was when I had good layout men on The Phantom Tollbooth (1970). I'd give a general trend, and talk it over with the layout man and say, "This is a general format; see what you can do, working in this general area." He'd go ahead and work with this material and I'd go in and check it over.

GRAY: [Reading from the list of written questions] "On relatively simple pictures like the Road-Runners, would you sometimes leave a lot of the work to Phil De Guard?"

NOBLE: Phil and I worked together on so many Road-Runners. He was a very thorough guy, and he liked to know exactly where he was going. at all times. Production time was very precious. So, we'd know the color scheme, for instance. One or two little notes, and that would cover the Road-Runners. On some of these zany shapes, I would do the shape, and then I'd use a colored pencil to indicate strata, to give him an idea of how this thing was broken down. Of course, I figured all pan lengths and stops and starts and positions and all that, from the exposure sheets; I did all the mechanics. A very important thing about doing really good creative design and layout work is to know your camera. I would always try to build up a rapport with any cameraman I was working with, so that I would know the capabilities of the camera. When Johnny Burton, Jr., was breaking into the camera field, I had a couple of run-ins with him, and so did Chuck, and so did Friz. I just had a donnybrook with him one time, I just laid him out, because he wasn't going to go by something that I had indicated on the exposure sheet.

GRAY: Why did he decide he didn't want to?

NOBLE: Because he didn't think it was right. After we had that settled, I took another tack with him. He was a very smart cameraman. You remember High Note (1960) with these little animated notes, and the hazy, transparent colors around them? I got this idea of doing it that way, and I made these little patterns, out of theatrical gelatin. Then I went into Johnny Burton, Jr., and I said, "I want you to fix this up for me." Between the two of us, we worked this on the camera, so that at the proper distance, he could shoot through this on the black and white paper, and we'd get these designs down below—soft edges. We could do all sorts of things with them in varying the distance. He got the idea of what I wanted, and so he worked out the mechanics, and how to hang this piece of black cardboard below the lens, and all this and that. Once he knew where we were going on that, he was very ingenious, he got real excited about it. We finally worked out a great rapport and we did all sorts of things. The crazier the thing was that I'd come in with, he'd work it out, and we'd get it on the film. This was a cameraman who wanted to be creative; a lot of them want to punch the button and get their footage out. And a lot of studios today won't give time for a creative camera job, where you have to do a double or triple or quadruple exposure.

GRAY: A minute ago, you said "black cardboard."

NOBLE: The colored gels had to be hung on a little black cardboard suspension, at the proper distance from the lens. We took a couple of color tests and found out the best place for it, and so forth. That's how we shot it. There was no paint, just black and white down below, with the notes; the color was up on the gelatins.

GRAY: The same thing was used in What's Opera, Doc?, too, wasn't it?

NOBLE: Yes. I had an argument with the cameraman on that: it was a different cameraman. I punched a hole in a piece of blue celluloid one day, and I was experimenting with this stuff, and I saw this made a spotlight. I took it into the cameraman, and I said, "Why can't we do something like this?" I argued with him, and I got him to try it under the lens, and we made a spotlight out of it. They knew when I went in that I had a definite reason why I was asking that question. Can we do this, can we get this effect, can we double-expose, what percentage do you want me to expose on the sheet and split it, and so forth. so that when it got to him, it would say 50 per cent, or 40 per cent. exposure, or whatever it happened to be. Particularly when you're working with film, the only way you can have ideas is to know how to exploit the possibilities in the medium. I was always trying something, and sometimes it would backfire. That's what kept the job interesting all those years.

GRAY: I'm assuming that you probably saved some time, on some cartoons like the Road-Runners, where it was pretty straightforward and the background man would know what to do, and that possibly would have left you more time to experiment with other things, like What's Opera, Doc?.

NOBLE: Yes, I was always cheating on the time schedule. I'd be two pictures ahead or two pictures behind what was going into the bookkeeper. They had x-number of weeks per picture to move through. If I got a cheater through, and I could lay out the whole thing in a week and a half—like I could do some Road Runners, because Phil and I had done so many. I'd shorthand the thing through, and he knew exactly what everything meant. That's the reason some of those stipple bushes came through, because all I had to do was put three or four lines like this and swipe it with a smudge, and that meant a bush. That went very fast. He traced all of his own backgrounds, but finally we had a background tracer. He would tell her what he wanted traced and what he didn't. He'd lay in flat colors and then we'd take colored pencils and do the stratas—white and gray and pink and so forth. Lots of times I would lay this stuff out in colored pencil, and he'd know exactly where to go with everything.

We did the cheaters, and then we'd get some elaborate picture that took a heck of a lot of work, and we might spend seven weeks on it. That meant we both had to sweat like crazy, because we were enjoying the elaborate picture, and we had to make up the time on something else. We'd have what we called "baseboard pictures" that had mouse holes in them. It's sometimes kind of hard to keep a baseboard picture interesting. You get a chair leg, or a shadow, or some pattern. You just can't get away from that kitchen floor, even to pan on it, so what do you do? You put a diagonal pattern of big squares, so they can move in and out, so you can make the pan movement as the mouse goes across the floor. You may find that three-quarters of the footage is something to do with a cat and a baseboard and a floor and a mouse hole. You go like crazy on those so you can spend some time on something else.

GRAY: [Reading from the written questions] "In some respects, your work is similar to that of the UPA artists. At the time you were working for Chuck, what was your attitude, or his, toward the UPA studio?"

NOBLE: We thought that a lot of the UPA stuff was very interesting: some of Hubley's early stuff was extremely interesting. I'm not interested in his present spastic animation. One time I was talking with him and I said, "John, it seems to me that you're forgetting that you have an audience." He got kind of a stunned look on his face and he changed the subject. I knew John years ago at Disney's. I think his Moonbird was a charmer: it was so charming that he didn't get over it.

GRAY: He kept repeating it.

NOBLE: And not doing it nearly as well. I've always had a feeling of liking to stylize and work in patterns. In fact, I had kind of a run-in at Disney's, years ago, because I felt that animation was a flat form—designed flat forms. All of this stuff, charming as it is, like Snow White—everything rounded, and noodled to death—the backgrounds—! didn't think it was appropriate, relative to the medium we were using to support it. Visually, your designed areas gave you your depth, or whatever you happened to be working with; but it wasn't due to a carefully airbrushed turn. Long, long ago, I started to try to work in more of a patterned way, and approach. At one time, they wanted me to work at UPA, when they were starting up their studio. I forget what intervened; I probably decided I'd rather work at Warner Bros.

GRAY: That's a twist; usually what I hear is, "Gee, I'd have loved to work at UPA, the progressive studio."

NOBLE: I was there one time, for a week or something, when Bernyce Polifka was there; I don't even remember what I was doing there, or even if I was on payroll. But it just didn't work out.

GRAY: You mean the place wasn't quite right for you?

NOBLE: Something like that. I don't think that I have consciously looked at any given studio or given artist or anything like this, and said, "I'm going to emulate that guy." I'm too stubborn.

GRAY: When you have a strong belief in your own approach, you're probably less susceptible to being lured toward someone else's approach.

NOBLE: I don't think I even have that. It's what's appropriate. Many times I have designed a cartoon in a certain way which hasn't particularly pleased me but it seemed to be appropriate for that given cartoon. I can't think of any examples right now. Any artist or designer who gets so enamoured with his own work that he can't be self-critical is in a sad way. Each thing has to be a new adventure, a challenge.

May 31, 1989

BARRIER: I was surprised to see in the Warner Club News that you actually started at Warners in 1946, as a background painter.

NOBLE: I was painting backgrounds, right.

BARRIER: Who were you working for?

NOBLE: It was kind of a strange situation; I was painting backgrounds and doing layout, too, but I guess they gave me credit as a background painter. I was working with Chuck Jones; I worked with Chuck when I was in the army, because we were doing the Snafu cartoons. I had known Chuck clear back to the time of the Disney strike; actually, I can't remember when I met Chuck. In 1946, I was semi-replacing Bob Gribbroek. I worked there for a while, then I had an opportunity to go east—I was offered part of a filmstrip company in St. Louis, for the Lutheran Church.

BARRIER: Oh, so this was when you went to St. Louis.

NOBLE: That's right; someplace in that area. I can't remember exactly the chronology of the thing. But then I came back, and I guess Gribbroek continued to do layouts or paint backgrounds—he was painting backgrounds, too.

BARRIER: In the middle forties, he was painting backgrounds and Earl Klein was doing layouts.

NOBLE: That may have been what the arrangement was at that time.

BARRIER: But you said you were going to replace Gribbroek?

NOBLE: When I worked in St. Louis, and I'd been there a couple of years, I got a call from Johnny Burton, saying, "We have a layout job for you if you want it." By then, I was fed up with St. Louis, and also I was getting the shaft from my boss; I wasn't getting the portion of the business I was supposed to. I had started myself and built the department up to six men, and we were all doing filmstrips and things like that, and still I wasn't getting my portion of the company as promised. That's when I came back and started work with Chuck, and worked all the way through to the demise of MGM.

BARRIER: When you started in '46, you must not have been there very long.

NOBLE: Not long at all, no.

BARRIER: You mentioned at one point that you were at UPA when Bernyce Polifka was there, which would have been—

NOBLE: I didn't work at UPA.

BARRIER: But you did mention in the original interview about being there when Bernyce was there.

NOBLE: I knew both of them, [Gene] Fleury [Polifka's hustand] and Bernyce, and I worked with Fleury when I was in the army; we were both in the army—the Capra unit and Ted Geisel. I didn't work at UPA; they wanted me to come over and work there. I think Hubley was over there at the time, and a bunch of people. I chose to stay with Chuck. I forget what we were doing around then.

BARRIER: Why don't I go over what I know about your chronology. In '46 you were a background painter, and as you said, you left that job to go to St. Louis. From the information I have, you came back and started working for Chuck around May of '51.

NOBLE: That's probably right.

BARRIER: The first cartoon you had a layout credit on was Rabbit Seasoning, and the third was Duck Amuck.

NOBLE: I laid that out, and also painted the backgrounds.

BARRIER: Phil De Guard didn't do those.

NOBLE: No.

BARRIER: Those were the first backgrounds for one of Chuck's cartoons that had a strong element of abstraction.

NOBLE: Right. I remember I laid it out, and for some reason or other the production schedule was a little behind, and Johnny Burton asked me if I wanted to paint it. I worked in vacation; I was all alone in that building, besides the janitor, back in the corner of the building. The amazing thing about that building was that they laid the flooring upstairs right on the steel beams, so there was no ceiling. All the dust sifted through from upstairs, and every time anybody dropped anything, it felt like the roof was coming in. I'd go home every night, and I'd be dirty across my shoulders. Sometimes I'd have to kind of cover my work so it wouldn't get crummy.

BARRIER: Who was directly above you?

NOBLE: At one time, Benny Washam was. He used to have a big, round—I think it was a railroad wheel, a big steel wheel this big around, and just for the fun of it, every once in a while he'd get right over me and spin this thing. It'd finally come down with a bang.

BARRIER: So Chuck's animators were on the floor above...

NOBLE: Finally they consolidated all of them, and Benny and Abe Levitow and Dick Thompson and...let's see...Ken Harris, we were all right there at the end of that first-floor hall. And Mike Maltese. The unit was all together. But Phil De Guard retained his background painting upstairs, because he had a north light. I was on the light well; if I leaned back far enough, I could look up the light well and see the blue sky. That's about as much as I can remember about the unit there. About three light bulbs down the half-block half-watters. So you were coming in out of this blinding light, and it was just a black tunnel with little spots of light. Little by little, your eyes would get adjusted, and you'd find out who was there.

BARRIER: You started work there around May of '51 and left early in '53, shortly before they announced the studio would close.

NOBLE: That was just a coincidence; everybody thought I knew about it. I went and worked for John Sutherland. Selzer had refused my request for a raise, and John Sutherland was generous.

BARRIER: That must have been when you worked on Rhapsody in Steel.

NOBLE: Yes; the inaugural program for the big steel dome in Pittsburgh.

BARRIER: You came back to Warners around July of '55; were you gone that whole time to Sutherland's?

NOBLE: I stayed at Sutherland's; it took quite a long time to do the steel picture. I also did some commercials. Bill Melendez worked over there at that time, and I worked with him; we did a picture for the Sloan Kettering Foundation in New York, on cancer, the first picture being done on cancer. We had a lot of really kind of top-drawer things going over there. I think the steel picture was really a knockout. It starts with a meteor hitting the earth, and primitive man getting the first steel that way, or iron, and at the very end of the thing, it's a blastoff of a rocket ship, long before they had any rocketships. I designed this gantry and everything, to hold this thing upright, and had elevators going up and all of that—by George, it's the same thing they have down at Cape Canaveral now.

BARRIER: It sounds like the same sort of thing you did, too, for Hare-way to the Stars (1958).

NOBLE: Yes. And then the blastoff in the steel picture came,, and the picture ended as the guy was looking out the window, back at the earth, and finally the earth is only a star among many stars. Then I came back to Warner Bros., and started work with Chuck again.

BARRIER: That must have been when they had just moved into the studio at Burbank.

NOBLE: No, I was back at Van Ness. I remember I was told to pack up my stuff, and did I want this and that. We went on vacation or the studio closed for a while.We reported for work at the Burbank studio—old furniture and new paint. [As noted in Hollywood Cartoons, the move from Van Ness to Burbank took place late in the summer of 1955.]

BARRIER: When you came back in '55, the first thing you worked on, evidently, was What's Opera, Doc?, then Deduce, You Say, and the fourth thing you worked on was Boyhood Daze. You were gone again from late '57 until around June of '59, about a year and a half. I guess that's when you went back to Sutherland's for the second time.

NOBLE: I can't remember being away at that period. When we moved out to Burbank, I worked straight through there until the studio was closed. I believe this period was spent on the main Warner lot designing the Bell Telephone animation science series with Owen Crump, [Frank] Capra—"The Human Senses" and "Language."

BARRIER: That's funny, because in the Warner Club News they mentioned in late '57 that a couple of layout men were hired, and that's the point where your credits disappear from the cartoons for a while, and Phil De Guard got a lot of layout and background credits, and Owen Fitzgerald got some credits. You said in the earlier interview that you did go to Sutherland's twice.

NOBLE: I haven't any idea. I'm terrible; anything that happened yesterday, I forget about it. I'm always thinking about what's going to happen tomorrow. That's always been my attitude toward work. I didn't save much of anything I ever did.

BARRIER: Chuck has talked about the hostility that his more adventurous cartoons, like From A to Z-z-z-z (1954), received from the studio audience. That was one of the first cartoons that you did for him in '51-'53 that really departed from the typical Warner look.

NOBLE: I do have the feeling that the rest of the studio, meaning McKimson and Freleng, didn't quite understand what Chuck and I were trying to do, in terms of story and presentation.It just seemed "right" to design in this manner to fit a given situation or mood. Design must always be relevant to the subject. I was also always after Mike Maltese about all these mayhem gag situations, chasing around with axes and explosives and all this and that. I didn't think that this was psychologically good for the younger generation who were looking at them. I had many, many arguments about it; Mike would finally cringe when I'd come in the room and start looking at his storyboards. I'd like point at it and say, "Uh-oh," and he'd put his arms over his head like this, and say, "Uh-oh, I did it again." And lots of times, the stuff would be changed.

BARRIER: In the stuff that Chuck was doing in the late forties, after Mike became his regular story man, there's much more of a flavor of Mike than there is in the later cartoons, in the fifties. They feel much more as if Chuck's sensibility, and I guess indirectly yours, were affecting the stories.

NOBLE: It reached a point where Mike would have an idea, and I'd get a Xerox copy of Mike's story at the same time Chuck would. Chuck would say, "Do some thinking on this," in a sense, and he would be working on something, and then he'd gather up my material, and sometimes it would be worked back into the picture, and sometimes it wouldn't. This was particularly true of What's Opera, Doc?; his story line almost had to follow what I had created for the setup and story followthrough. When I got the Annie award, Chuck was very gracious and said, "I want to present Maurice's What's Opera, Doc." The little Ralph things, and all that, the stylization helped put it over into the realm of fantasy, so the shaping of a lot of the material—I know sometimes I would interpret some of Chuck's animation setups, I would restage it, and he'd be surprised when it hit the screen, because it wasn't exactly what he had in mind. But it always worked. I would always know what was going on in camera, and what was going on in the music department, and so forth, and if the musicians got so they needed a couple of beats, I could go in and restage, or cut the pan shorter, or make it a little bit longer, or something like that, and fix it up for them so it would work. Ted Geisel used to call me "the catalyst." I'd bring a lot of the stuff all together, as I did on his pictures. Eventually, I'd do a few sketches and show them to Chuck, and he'd say either "Go with it" or "Let's go a little bit in this direction," indicating one of the sketches. He always said that he could always pull me back from a certain position but he couldn't push me out. Now, where were we? Oh, the studio reaction. I remember when we did What's Opera, Doc. Friz came in one day—little short guy—and put his hands on his hips, and he looked around at the stuff I had on the wall, and he said, "What the shit!" And walked out of the room. I think that whenever we were going to preview one of our pictures, they'd wonder, "What's coming up this time?"

BARRIER: Would they sit on their hands?

NOBLE: No, no. There was a certain, shall we say, reserve. You didn't applaud their pictures, and they didn't applaud ours.

BARRIER: As a matter of course.

NOBLE: As a matter of course.

BARRIER: Regardless of the content or the style of the picture, you didn't cheer for Friz's pictures.

NOBLE: I found them a fairly amusing but standard diet. Never a real "lift" in content and approach. Once in a while I'd get kind of quizzical looks—"Why'd you do that?"—regarding Chuck's pictures.

BARRIER: Did you hear people complain that it was too arty?

NOBLE: No, they didn't; or else I was too dumb to recognize it, or too busy to pay much attention. I was so busy when I was at the studio that I didn't get around much. McKimson was upstairs and Friz was down the hall, and we came in in the morning and went out in the evening. There was not much interchange except at the story and director level. I did not particiipate at story meetings.

BARRIER: You weren't going down the hall and saying to Hawley Pratt, "What did you think of our latest cartoon?"

NOBLE: Oh, no. It just wasn't done. It was a strange thing.

BARRIER: You get the feeling the units were all very distinct.

NOBLE: Very distinct. I do think that McKimson was a highly underrated director. He had a certain simplicity and almost naivete; I thought a lot of his cartoons were absolutely delightful. Very simple statements; there was nothing very sophisticated about anything that McKimson did. But when the little kitten would put the bag over his head and say, "Oh, father!" when he was disgusted with him, it was the cutest darn gag, and it was so appropriate, and it was well timed. And this darned rooster [Foghorn Leghorn] that McKimson was always working with—marvelous character. They were kind of like Aesop's Fables, in their simplicity. It always kind of irritated me that Chuck and Friz [would take a condescending attitude, as if to say] "Well, okay, that's another one of McKimson's pictures."

BARRIER: They definitely looked down their noses at him.

NOBLE: Oh, they did. And I sat there laughing my fool head off. Maybe I'm simple-minded, I don't know. I designed one picture for McKimson, towards when the studio was starting to close; it was a real far-out thing. McKimson just loved it.

BARRIER: He loved your work.

NOBLE: Well, how the picture turned out.

BARRIER: Bob definitely liked his own cartoons.

NOBLE: I'm one of his fans—which may sound strange. In a sense, there was no strain in McKimson's cartoons. The story line was very direct, very simple, and that was it.

BARRIER: His were simple, and Friz's were obvious.

NOBLE: I think a lot of Friz's stuff was by rote; he wasn't adventurous at all. He was a make-my-money, keep-my-nose-clean type of person. This is what I will hand to Chuck, that Chuck was always experimenting, to find things out, and he gave a lot of us opportunities to try things. This is what made Chuck's cartoons outstanding.

BARRIER: And, of course, that's one reason Friz was so highly regarded by management: He didn't make any waves.

NOBLE: No waves at all.

BARRIER: I have real reservations about Friz as a director, but I've always liked him as a person.

NOBLE: He's an interesting, feisty little character.

BARRIER: He's very open and direct and natural.

NOBLE: Oh, there are no frills on Friz.

BARRIER: Chuck can be not that way.

NOBLE: The crap that Chuck's turning out now is just appalling. It's hurting his reputation, terribly. Everybody's holding their nose and saying, "What the hell's he's doing?"

BARRIER: The last time I saw Chuck, in 1986, it was very revealing, because he kept talking about other people, and saying, "So-and-so can't draw any more." I thought Freud would have something to say about that, because to me, what's really conspicuous in his work in the last ten or fifteen years is that his own draftsmanship has gone downhill. He was such a wonderful cartoonist, and so precise, and everything seems so much slacker now. I gather from people who have worked on the films that he doesn't give the attention he needs to, to that part of it.

NOBLE: He doesn't give it the attention; he's too busy being Mr. Jones. He's always running off to England, you know. I heard that he started to work on [Who Framed Roger Rabbit], and then he was insisting that Roger Rabbit look like Bugs Bunny, and got fired off the production. He's now—at least Chuck told me this—the representative of Warner Bros. cartoons, and contact man; they've sent him to Australia and I don't know where else. He wanted me to do the illustrations for a book he was working on; I forget what the story was [probably William the Backwards Skunk]. I looked at the drawings, and how inferior they were, and the story, which he had written, didn't seem to hitch up with the drawings. I had it for a couple of weeks, and went through it, and I finally made some written suggestions on my Xerox copies that I had of the book, and he flipped his gourd at me and told me he'd sold the book and that's the way it was going to be. I said, "Well, Chuck, I just can't work on it." That was the last real contact I had with Chuck, as far as working goes. He did come and introduce me at the Annie awards, at my request, but I haven't seen—well, I saw him once. I started to work on a new Dr. Seuss, and Chuck and Ralph Bakshi and I were down there at Geisel's—

BARRIER: Ralph Bakshi? That's an interesting combination.

NOBLE: Somehow or other, through Turner Broadcasting, they're doing this thing of Dr. Seuss. Chuck originally called me and said that Bakshi was going to be the producer, and if I was interested, call Bakshi. I went out there and talked. Bakshi's reputation of being, shall we say, far out—I think he was a little confused about "what am I going to do with something like this?" It turned out that Bakshi and I got along just great. I did sketches and helped develop the story and all this sort of jazz. But he was standoffish, of the whole thing; he was busy doing some teenage stuff for cable TV. The story is called The Butter Battle Book; fundamentally, the story doesn't have enough guts to carry it as a motion picture. It's just this one episode of back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. So songs had to be written and thematic material had to be developed. I had what I thought were a lot of good ideas, and so did Ralph. I took them down to Ted, and Ted threw us back, and was very disagreeable. That was around last Christmas, and I didn't go back on the production. I kind of overdid it, and the doctor seemed to think I ought to take it easy. I didn't hear anything from Ralph for a long time, and then he called me up and told me to come on out, he wanted to talk to me. He had another feature going, and he said, "It's going to be going in just a couple of weeks," and I talked to the gal in the bookkeeping department, and it was all a go, and how much money he'd pay me. Then I didn't hear anything and didn't hear anything; finally I got a call from his secretary, who said, "Ralph wants to talk things over with you." I said okay. She said, "He's in Cedars-Sinai hospital." So I went out to Cedars-Sinai hospital to see him; he'd been in an automobile wreck—two broken legs, a broken arm, a broken hand. He was all in plaster casts and steel braces. I've only talked with him once since, and I'm hoping that the production will go, because it's very strange. He's a very, very sensitive pussycat when you really know him.

BARRIER: I didn't find him that way when I was dealing with him. When I was writing a long article on Fritz the Cat, he made it very difficult for me.

NOBLE: That's another aspect of him. I know he really blasts people and things and situations, but either over the years he has mellowed or he thought maybe I was going to be able to pull this Dr. Seuss thing together for him; but he thought enough of me to call me up and want me back on another picture. I think this bravado he puts on is a defense mechanism. We'd sit and look at, say, some beautiful Degas prints he had, and he'd go all to pieces looking at them, and tears would come into his eyes. It wasn't put-on at all. [But] he doesn't want to look like a softie from the East Side.

BARRIER: You're in a position where, if he turns out to be a bad guy, you can walk away from him.

NOBLE: Well, this is it. He has always treated me with the greatest respect and consideration.

BARRIER: I've heard that he will do that with people that he really wants to get on his staff, but once you're on the job, it's a little different.

NOBLE: I've heard that, too. Somebody said something to me along that line, and I said, "I've got a thick hide." I've been around this town too long. I've taken blows from all sorts of people. The thing is, when you're working on a picture, it doesn't hurt what kind of shit's thrown at you, it's what you're doing that's the important thing. You just slough it of—fthey've had a bad day, or they've gotten kicked someplace, so they're going to take it out on you. I always turned the studio off when I went out the door. I didn't carry it around with me, because the only time you can do anything is when you're sitting in front of your drawing board, putting the thing together. I'd naturally think about things, if I had a problem; sometimes I could solve something away from the board, and come back and draw it.

BARRIER: You talked earlier about getting a Xerox copy of Mike's story sketches at the same time Chuck would; but going back to the early fifties—

NOBLE: You wouldn't have that, no. I would go in and see the board; I would check over the board. I think sometimes Chuck would gather Mike's sketches all together, but he didn't have time to work on it, so he'd say, "Look this over," or something like that; and eventually it would be handed back to Chuck. So I'd have a formulation of some ideas to feed back to Chuck as he started to develop his story line. I think this was the way it worked. Then eventually, I know, I had some Xerox copies of some of Mike's stuff.

BARRIER: I know that sometimes they photostated an entire board.

NOBLE: Usually the photostats were model sheets and poses and sometimes (at a later date) when "farming out" hunks of pictures. This was scene by scene, they ran through the Xerox machine. I had a few of those; I might even have some now.

BARRIER: Were you ever present when Chuck would go over a board with the animators, and go through the entire story for them?

NOBLE: Oh, yes.

BARRIER: You were ordinarily present.

NOBLE: That's right. The way it would work, Chuck would take the story, and lay the whole thing out, and time it, and it would be all in his sketches. He would get the whole thing together, then call the animators in, and he had decided which animator was going to have which scene. He'd go through the whole story, and I'd stand in the background, and kind of make mental notes who was getting what. In the meantime, I may also have started sketching, too.

A character layout drawing by Chuck Jones for What's Opera, Doc? Courtesy of Willie Ito. |

BARRIER: So when he was going through the story, he would show them his layout drawings rather than—

NOBLE: He would open the scene and show his layout drawings of the character, telling the story, the extremes that he wanted, and so forth.

BARRIER: To all the animators.

NOBLE: The whole group, at one time, so they would have the general construction of the whole story. This was a very good idea, because many times in the studio, somebody would get a scene, and they did not know where it fits in. So the whole crew would stand there, and Chuck would go through the whole thing with his drawings, holding the scenes in consecutive order.

BARRIER: So he wouldn't be showing the storyboard.

NOBLE: No, that long since had been put aside.

BARRIER: And I would guess that even though he was showing the animators the whole story, he would later show each animator individually his scenes.

NOBLE: Oh, yes. They would come back in, after they got the scenes, and he would call them in as they worked on scenes; or he would hand out the first scenes at that meeting, then he would call them back in individually and give them other scenes that developed.

BARRIER: But he would have the whole picture laid out.

NOBLE: The whole picture would be laid out, and usually "timed." I think this gave Chuck's pictures unity..