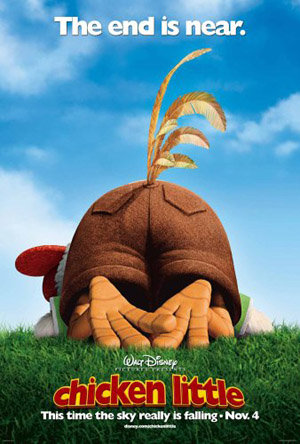

COMMENTARY

Plucked

Chicken

Little is the third elaborate and expensive industrial product

(I almost said "movie" or "film") whose principal

fabricator (I almost said "director") was Mark Dindal.

It is an odd item, even by the warped standards prevailing in Hollywood.

Chicken

Little is the third elaborate and expensive industrial product

(I almost said "movie" or "film") whose principal

fabricator (I almost said "director") was Mark Dindal.

It is an odd item, even by the warped standards prevailing in Hollywood.

Big-studio movies now cost, on average, around $64 million, and some, like the new King Kong, cost well north of $200 million. To expect any kind of artistry in most such films is simply not realistic. I wrote eight years ago in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age that the amounts associated with a film like The Lion King—production costs, box-office receipts, ancillary income from licensing and sequels and a Broadway version—were so huge that launching such a film had come to resemble introducing a new model of an automobile. That is true even more today. With so many dollars at stake, studio bosses are more intent than ever on managing risk, and so they hire compliant people who are willing to approach filmmaking as if it were not a job for an artist but a complex engineering challenge instead. Mark Dindal is from all appearances exactly that kind of director. That is presumably why Disney hired him to direct Chicken Little, a computer-animated film that marks the end of the studio's long allegiance to hand-drawn animation.

Dindal's cooperative attitude evidently trumped the poor performance of his previous two features, including Disney's own lamentable Emperor's New Groove. According to the New York Times, Dindal's original story line for Chicken Little concerned "a young girl who went to summer camp to build confidence so she wouldn't overreact." When David Stainton, newly installed as head of Disney animation, rejected that idea, Dindal obediently went back to work and turned the story "into a tale of a boy trying to save his town from space aliens." If, as seems likely, Dindal had no emotional commitment to his original version of the story, he certainly betrays no such commitment to the version that reached the screen.

Chicken Little's "tale" is like a negligible comic-book story—I remember reading such hacked-out stuff in some of the Dell funny-animal titles of the fifties—but that's not the problem. Gifted directors have always found ways to transform crass material into individual statements; that interplay between art and commerce is one of the things that has made the best American studio filmmaking so exciting and interesting. There's nothing like that in Chicken Little. To a remarkable extent—I can't recall anything comparable, at least not when an animated film had the faintest claim to respectability—Dindal stayed outside his story and his characters, manipulating them mechanically. For almost the entire length of the film, there's not a trace of the director's personal involvement in his work.

Such cool objectivity may have commended Dindal to his superiors at Disney, but a director who distances himself from his film reduces rather than enhances his control. Because Dindal had no intuitive grasp of his story, Chicken Little's rhythms are jerky—the film hurtles through what is supposed to be comic action, stepping on its own jokes, then abruptly goes limp at what are supposed to be heartfelt moments. Those moments in particular are loaded with superfluous dialogue; this is surely the talkiest feature cartoon ever. The whining chicken hero evokes Woody Allen, but that's not why he talks so much. All of Dindal's characters chatter unceasingly because there was no other way that Dindal himself could know what they were supposed to be thinking.

It was only at the very end of Chicken Little, during an over-the-top parody of a "Hollywood version" of the story, that I sensed an emotional connection between director and film; it was then that I laughed for the first time. Mark Dindal should be making full-blooded satires, rather than kiddie films full of bogus sentiment, but I doubt that he can find such work in present-day Hollywood. That's too bad for him, and for us.

A postscript: I saw Chicken Little in 3-D at a theater on Broadway. I'm glad I saw it in that format, but 3-D doesn't add a lot to the viewing experience. Only a few scenes include effects that seem to have been designed with 3-D in mind; otherwise there's only the enhanced illusion of depth that I'm told is relatively easy to achieve when computer-animated films are translated into 3-D. There's certainly nothing comparable to the enrichment that Imax 3-D adds to The Polar Express. The lesson being, of course, that if you start with a good film, 3-D may make it even better, but if you start with something as cold and dead as Chicken Little, 3-D can't bring it to life.

[Posted December 12, 2005]